The Dancing Fool and the mundus inversus

Abstract

The fools adorn Psalters, Books of Hours, and romances of the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries. They teem in the initials, miniatures, and illuminated margins of manuscripts. Specific visual features identify the fools as such and describe their nature. With extensive knowledge of ancient, biblical, patristic, and historical sources on madness, dance, and music, with dazing originality, illuminators invested great care in producing these figures of the mundus inversus and in the transmission of the scholar model they personified.

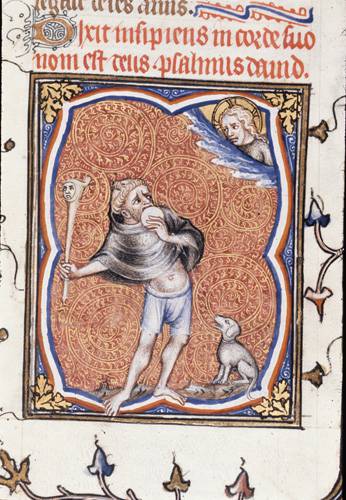

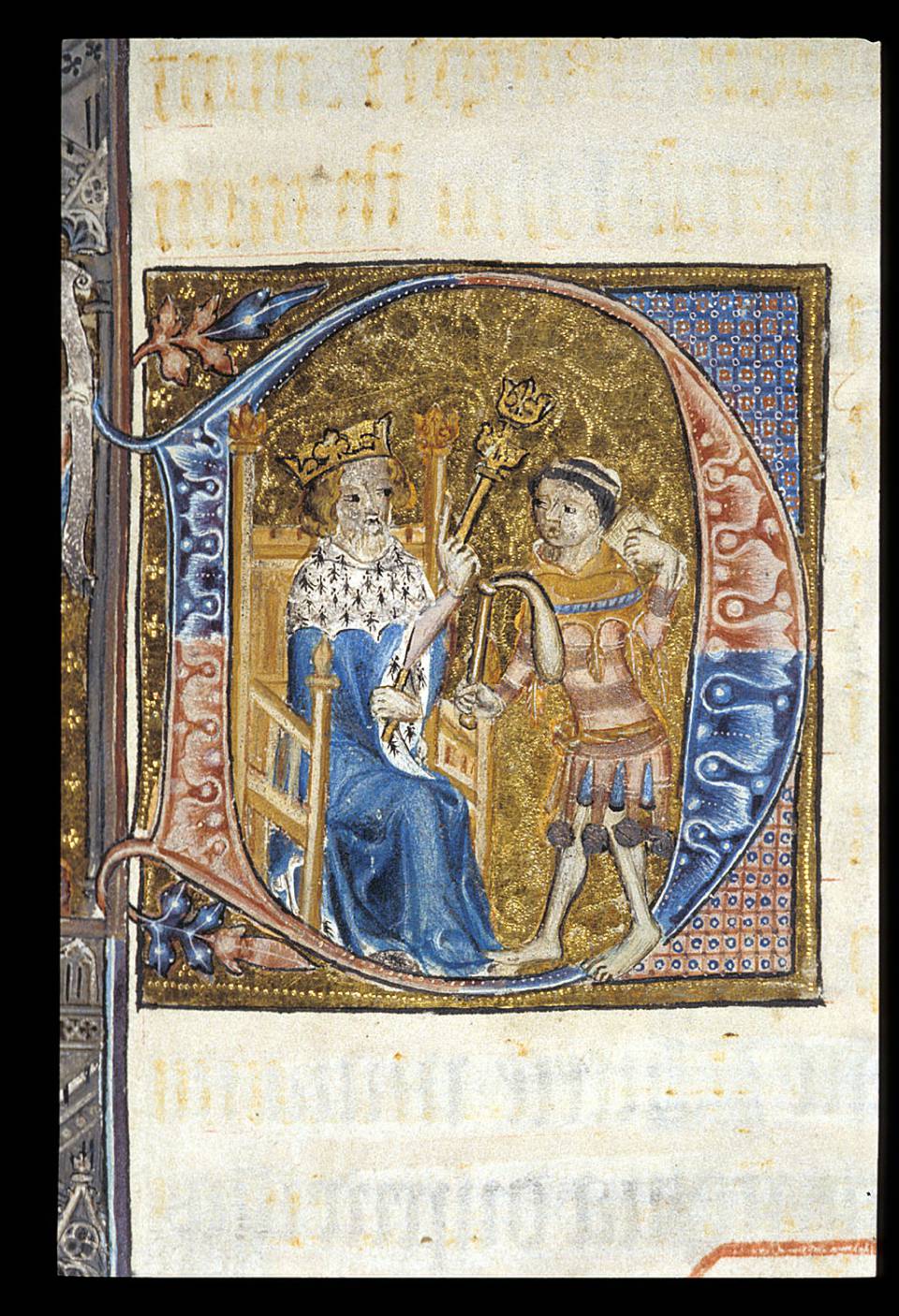

In the medieval literature, madness means nonsense and the insipiens or the fol is consistently defined in relation to wisdom. This madness is twofold, positive and negative, natural and artificial, and concerns both the soul and the body. King David conveys in this literary and iconographic genre visual and moral power to the fool’s figure, who becomes related to music, dance, rhythm, and harmony. Thus the initial letter of Psalm 52 (53) “Dixit insipiens” opposes in new ways the moral virtue of David to the fool’s sin and vice.

The madness of religious inversion is also that of the Fête des Fous. This ritual organized by the Church reverses the church hierarchy, parodies the church service thorugh dances, games, banquets, the Office de l'Âne, and the Évêque des Fous. The figure of the fool is ambiguous also in terms of political power: it can both condemn and authorize inversion and staged disorder.

At the end of the Middle Ages the jesters dance farandoles or the moresca in groups. They also participate in danses macabres. Always ambivalent, they are major figures of court festivities and reveal and relieve through laughter and macabre social tensions and the imagined nature of life and death themselves.

Einleitung

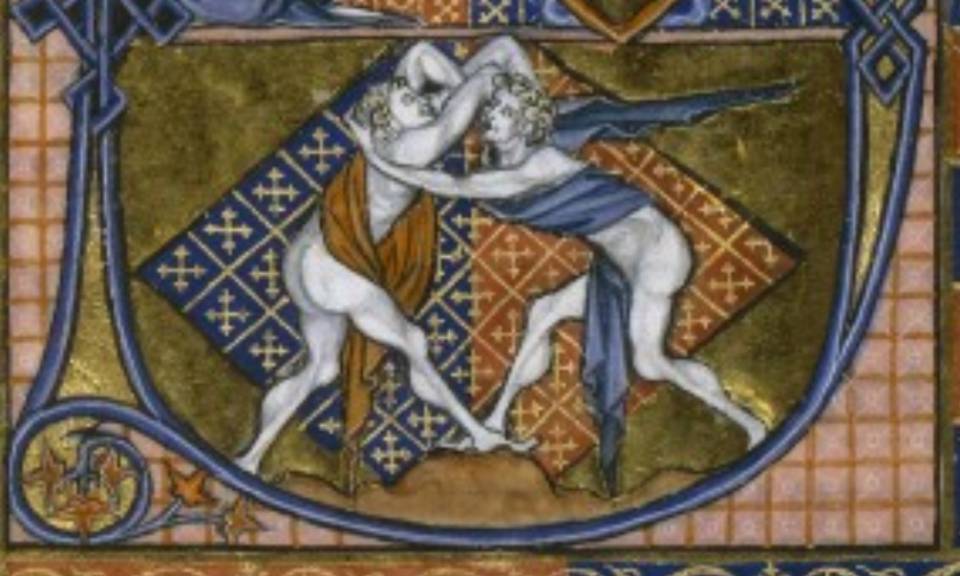

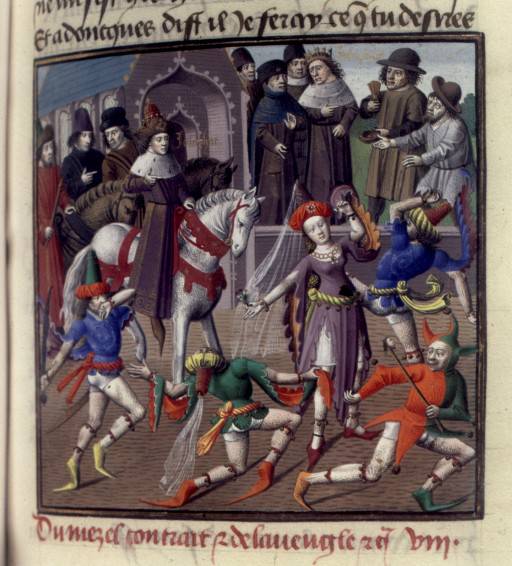

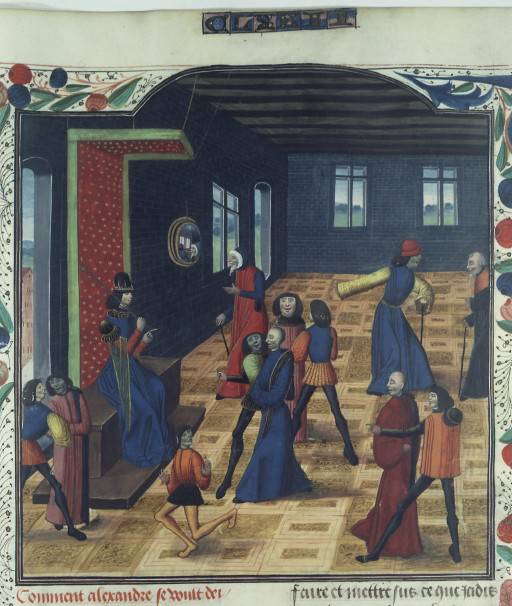

Fools are among the characters found in fourteen and fifteen century illuminated manuscripts. Although not in great numbers, unlike the angels for example, fools regularly appear intertwined in initials, within miniatures, and on page margins. They occur mostly in psalters and books of hours and at the turn of the fifteenth century they begin to appear in romances, such as the Roman d’Alexandre (The Romance of Alexander). Illuminators gave fools clearly identifiable visual features: they are shown tinkling bells and jingle bells, or playing bagpipes; they talk, shout, or sing; and above all their bodies are always in motion, an “inversed” kind of motion, in which their bodies twist in opposite directions, while they jump, frolic, and dance around, alone or in a disordered farandole. Fools embody inversion. The concept of a mundus inversus is typical of medieval culture and society, in the sense that any form of order, whether political, religious, or social, incorporates chaos. In the troubled context of the fourteen and fifteen century French and English kingdoms — the Hundred Years War, the papal schism, plague epidemics, and social unrest — the ecclesiastical and political elites swung between tolerating and even organising the celebrations of inversion, such as the Feast of Fools, and attempting to restrain them, often without much effect. This ambivalence could explain why in the visual arts dancing fools are always related to authorities and rulers, such as kings, dukes, or bishops. The fool’s ambivalent and inversed relationships are reminders that in the Middle Ages madness relates to wisdom — and less so to reason.

The miniatures reflect the culture of inversion peculiar to the medieval era, seen in the representations of jumping and dancing fools. They also bear witness to the visual creativity of miniaturists on how to evoke movement through static images by producing ancient forms of “cartoons”, a skill rooted in a deep knowledge of the Antique, biblical, patristic and historical fundamental concepts on madness, as well as those of music and dance. This approach shows how the association of madness with music and dance was a mode of understanding and interpretation of the human being — creature of God — within the medieval Judeo-Christian culture. It also reminds that images were not reproducing reality, but were — in the words of the art historian Pierre Francastel — a type of “figurative mode of thinking”,1 that is to say thinking the world and the society in images according to received cultural models, such as King David, Christ, or God. The study of madness in and through images of dance and music reveals the depth of theological and anthropological reflections on the human being and his Creator carried out by both miniaturists and their public.2 Far from being just an entertainment for readers, the “little dancing fools” perpetuate elements of the scholarly culture, so much so prestigious as conveyed through books, strong roots of the medieval culture.3 From this major cultural foundation the miniaturists addressed by the the believer, ideally a literate person, versed in the arts of dance and music. They seem to have chosen a wayward means to discuss through images the questions of Man being made in the image of God and endowed with a body and a soul, rationality, and language. By creating wondrous figures, they appealed to the visual and mnemonical power of images to enlighten the reader on the matters of madness and wisdom.4

The analysis performed here builds upon the following questions: How and to what ends are the fools featured in relation to dance and music in medieval illuminations? What are mirroring the images of dancing fools ?

Dancing and music making fools depicted during the fourteen and the fifteen centuries are not mentally ill, but they simulate madness for religious and social reasons in accordance with the Christian calendar. Four depiction types prevail: (1) the senseless creature jumping around and gesticulating in front of King David, (2) the processions of the Feast of Fools, (3) the farandole of fools and the morisque in royal and princely courts, (4) the dance macabre.

I. “Madness” and “music” or the common principle of inversion

1) Madness and wisdom: the “ambiguous ambivalence”

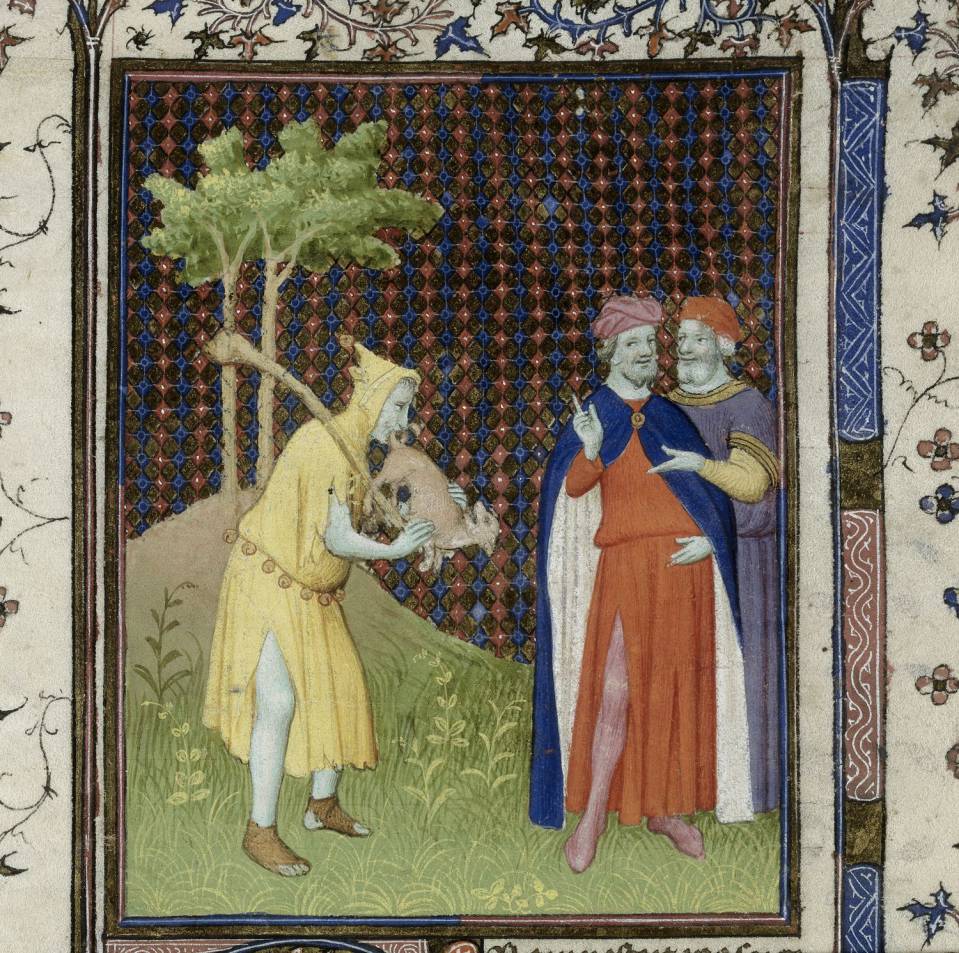

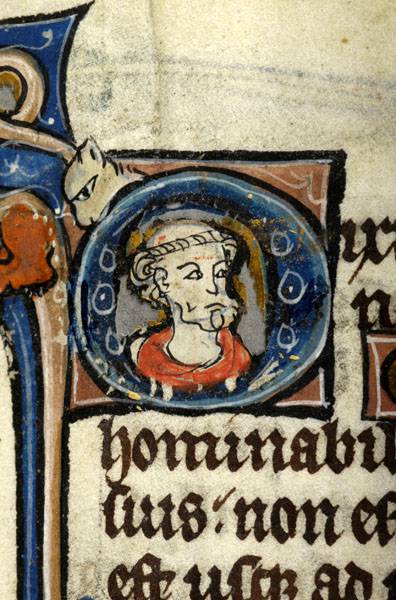

The study of madness as represented in medieval images is never without the risk of being anachronistic. On one hand, nineteen century historiography created the romanticized “post card” image of the court jester,5 and we need to regain critical distance by rereading the medieval textual and iconographical sources and newer scholarly research, such as that of Jacques Heers6, Danielle Jacquart7, Muriel Laharie8, Jean-Marie Fritz9, Max Harris10, or Olga Dull11. On the other hand, the definitions of madness given by language dictionaries are framed by an epistemological perspective that, since the seventeenth century, opposes it to reason and makes it an issue of psychiatry, as expounded by Michel Foucault in his Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason.12 This shared history of madness and rationality does not correspond, however, to what appears to have been the medieval perception of madness, seen as “nonsense”. In medieval medical treatises, as well as literary, theological, and juridical texts, madness has two faces, one positive and the other negative, one natural and the other artificial, and it is defined exclusively in respect to wisdom.13 Jean-Marie Fritz portrayed how since Greek and Roman antiquity the wise man had several fool types as counterpart.14 The first fool is so by nature, his state being one of both mental illness and innocence. The second fool is one who doesn’t known God, his folly being absence of reason (in-sania, in-sipientia, de-sipientia, a-mentia, de-mentia) and source of his various name: insipiens, stultus, or fatuus.15 The third fool type is the wild madman, in behavior and reasoning, possessed by violent passions (furor), which shake his soul and body. In French vernacular languages, the opposition between insania and furor is made by through the words dervé, forsené, and fol. The etymology of fol is found in follis, a “pair of bellows”, a “bag full of air”, in other words “empty head”.

The duality of madness is a complex “ambiguous ambivalence”, that varies with the authors and contexts of descriptions. An excellent illustration give the hermits, heretics, and religious order founders of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, those “Fools of God” whose faith is excessive to the point of madness. In the context of the Gregorian reforms inspired by the Oriental Christianism, such were men in love with God, like Saint Bruno (c. 1030–1101), founder of the Carthusian Order, and Robert of Arbrissel (c. 1045–1116), founder of Fontevrault’s Abbey.16 The bishop of Rennes, Marbode (1096–1123), describes Robert of Arbrissel exactly in terms of an insipiens: “An abject outfit thrown over flayed skin, naked feet, unkempt beard, hair cut short, you advance into the crowd and provide a formidable spectacle; only the club is missing to give you the airs of a lunatic [lunaticus]”.17

Regardless of madness type and name, it is located in the soul and is connected to the body, the very places where music takes place, and our aim here is to present the dancing fools in connection to music.

2) “Musica”: Antique science and biblical wisdom

Musica is one of the seven liberal arts, legacy of the Athenian paideia, and consisting in the trivium – the sciences of language: Latin grammar, rhetoric, logic – and the quadrivium – the sciences of numbers or mathematics: arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, they were studied in monastic, cathedral, and urban schools. Since the thirteenth century, they belonged to the curriculum of the Faculty of Arts.18 The aim of this activity was the divine Logos: expressing it through liturgical chants, copying and decorating it in manuscripts, and ultimately interpreting it.19

Musica is a mathematical science based on the Pythagorean theory of proportio,20 itself based on the “harmonious numbers”, which correlate sounds on a rational basis. It contributes along with ratio to a sound judgment by senses and intellect — we perceive here a link to foolishness and wisdom. This science is based on measured movement and refers to “the musical art audible to the human ear” through words, sounds, rhythms, and modes.21 Plato defines it as any form of art capable of generating order and harmony, such as chant, dance, or poetry.22

The ancient and scholarly musica seems nevertheless different from the musica of the fool in medieval images, who plays the bagpipes or shakes the jingle bells while proffering mute, but readable, words. Moreover, with what kind of “music” are we dealing with, when the images relate it to madness? Is it harmonious, sonorous? Why do miniaturists play with this paradox, particularly in books intended for the educated elites — clerics and nobles? And what devices do they use to visualize the paradox?

Two relationship types help understand the paradoxical association in images of musica and madness. One is musical, the proportio described above,23 while the other is rhetorical, the inversio. In rhetoric24, inversio is better known as permutatio in Latin and allêgoria in Greek, and is a verbal construct that means something different from what is manifestly stated.25 Inversion represents the essence of madness: the contrary of wisdom and the catalyst of mundus inversus. Madness operates through inversion in the realms of extremes, beyond proportion.26 It crosses all boundaries, insofar as it embodies at times an excess (of pride, for example) and at other times a deficiency in respect to a norm (lack of piety). Madness is defined by one’s relationship to the world and to God. The Book of Wisdom, 11: 20-22, defines it in musical terms: “But you have disposed all things by measure and number and weight. For with you great strength abides always [...]. Indeed, before you the whole universe is as a grain from a balance [...].”

As for dance, it is a kind of corporal expression based on rhythm27 and subject to the same arithmetical and geometrical principles as music, embodying the harmonic, organic, and rhythmic musica. In medieval images the “solo dance” is represented by a raised leg or gesticulations, while collective dances take the form of farandoles, carols, and circle dances.

Based on these definitions and rhetorical principles, we will look now at the medieval images of the “dancing fool” in religious contexts: the insipiens and King David in psalters and books of hours, and the liturgical ritual of the “Feast of Fools”.

II. The madness of religious inversion: gesticulations and Feasts of Fools

1) The gesticulations of the insipiens before King David

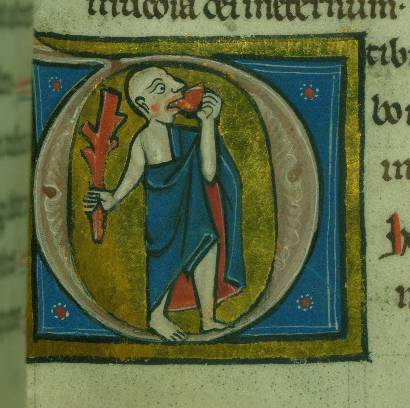

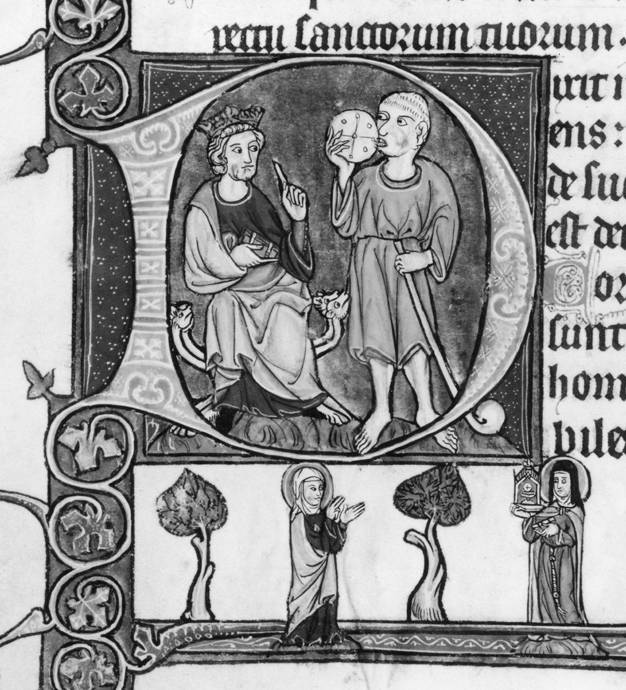

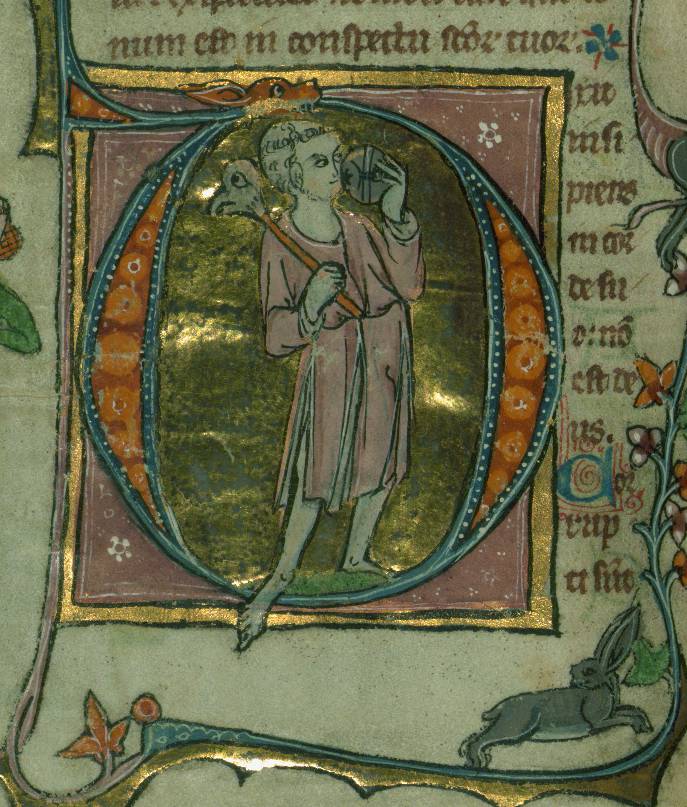

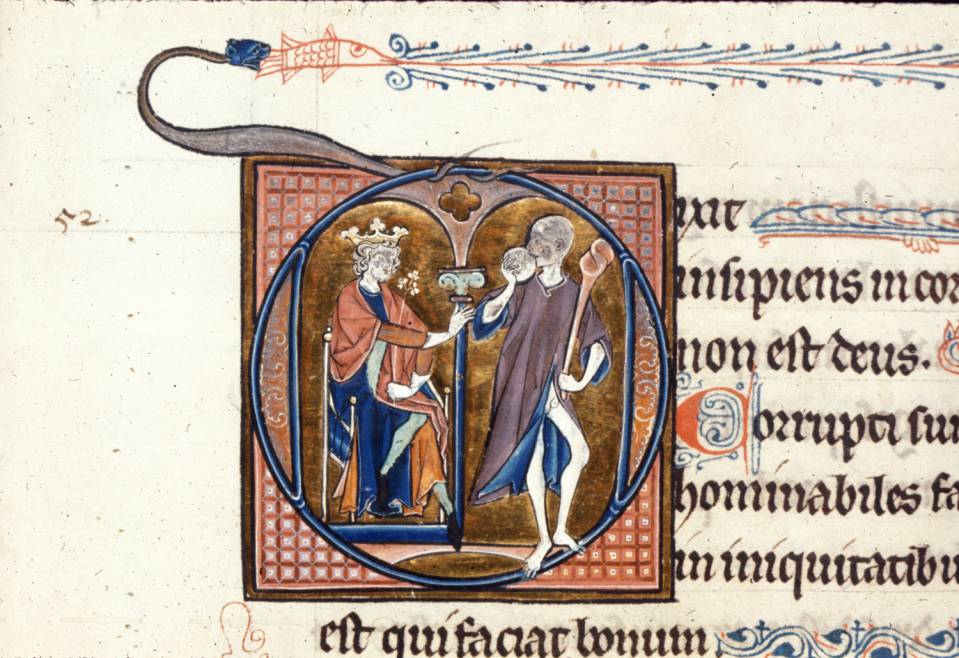

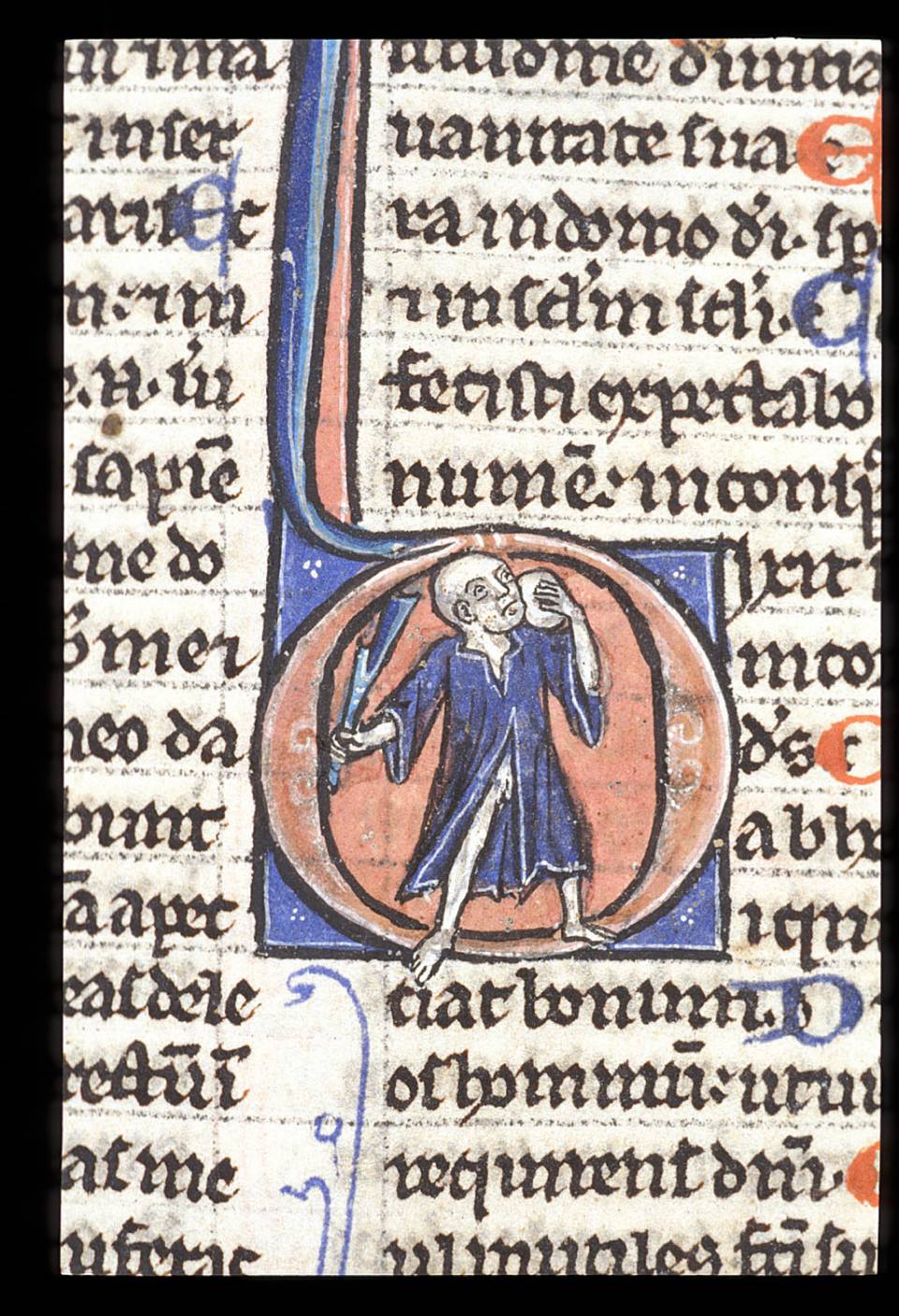

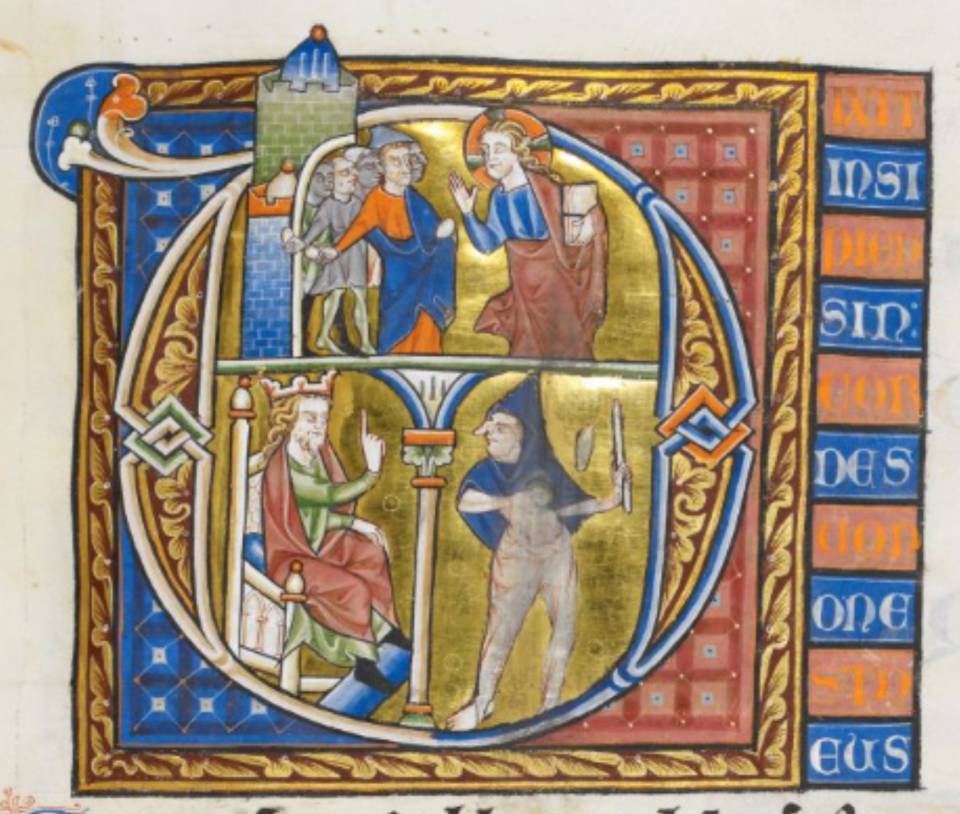

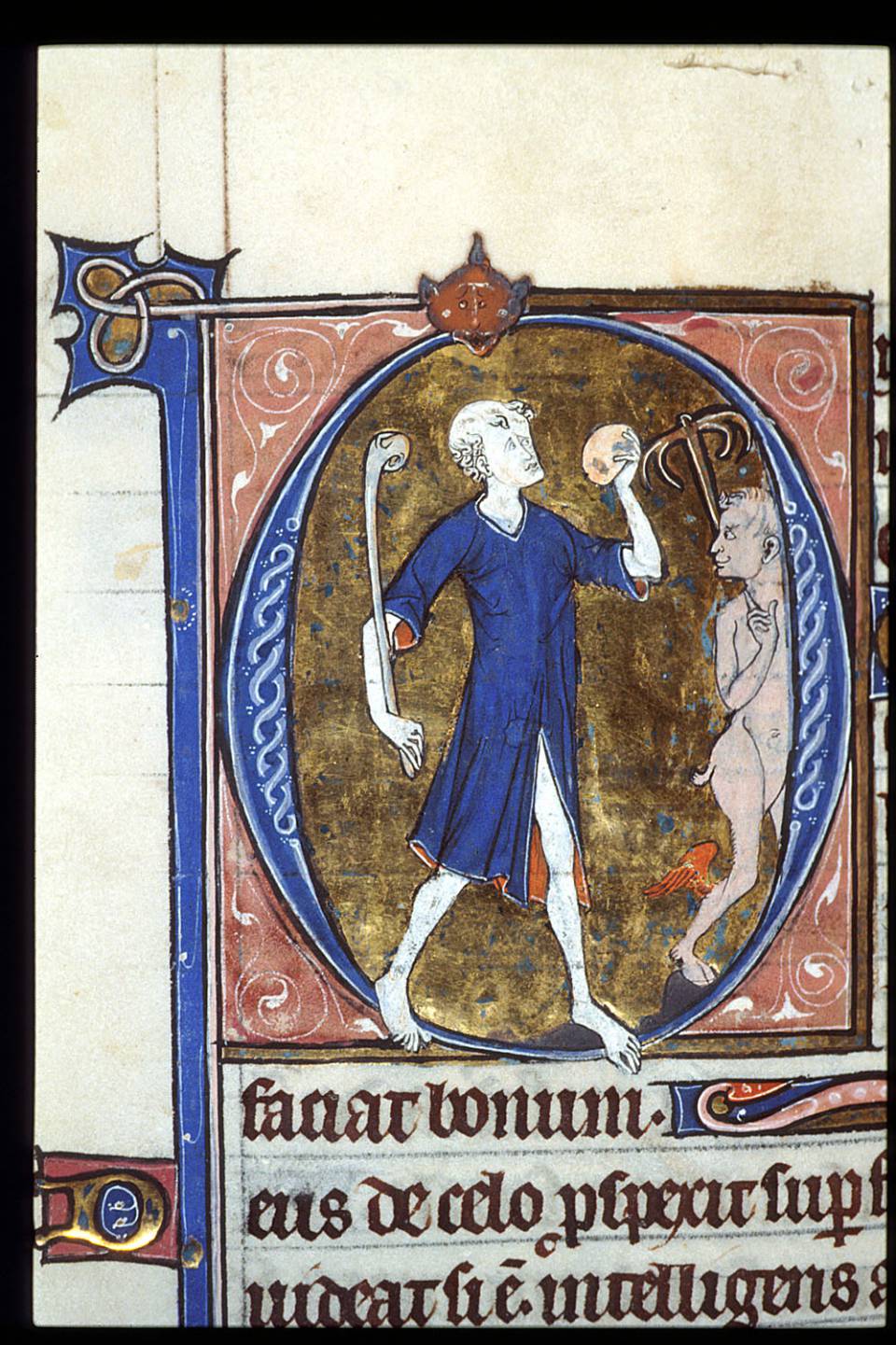

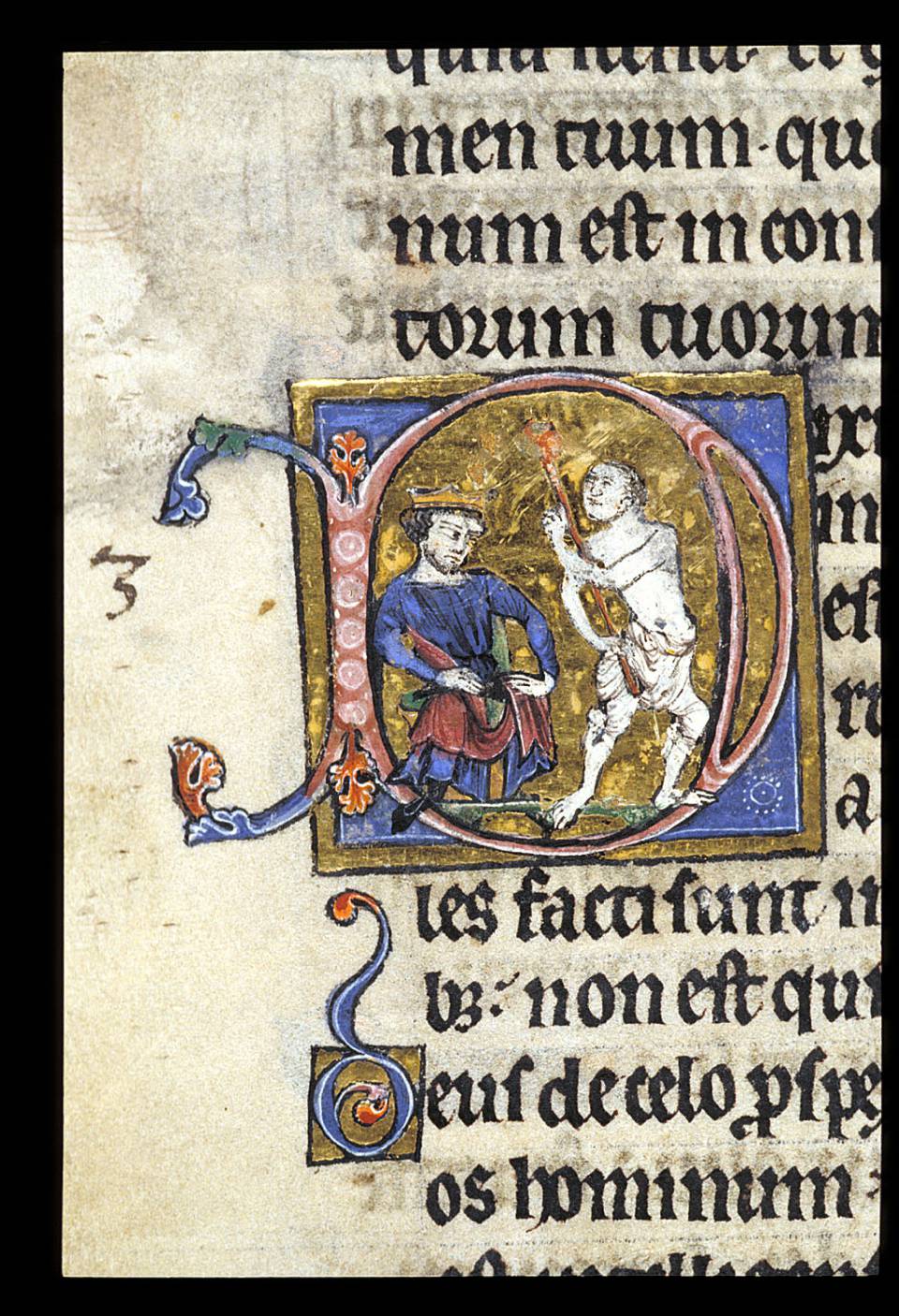

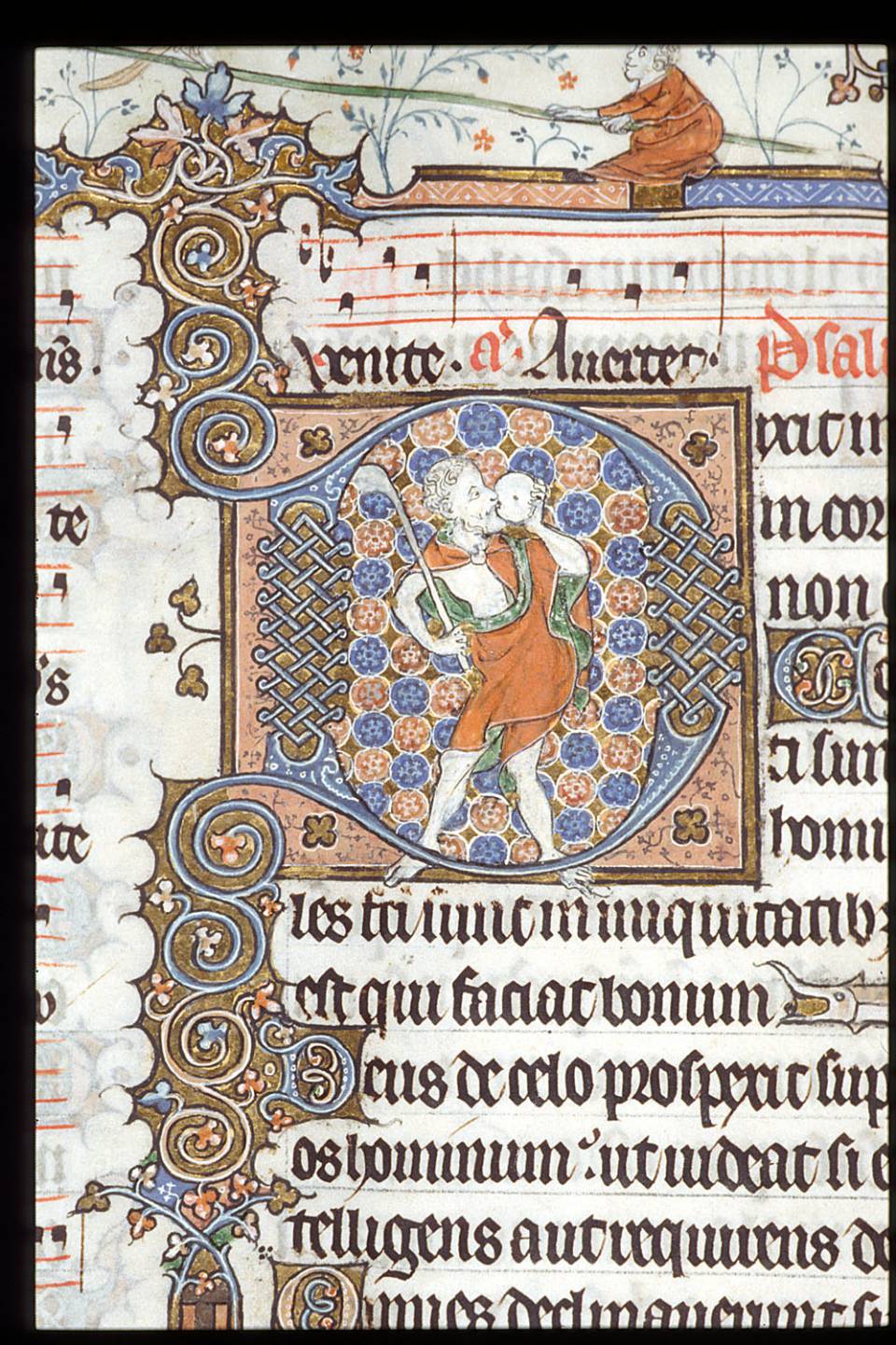

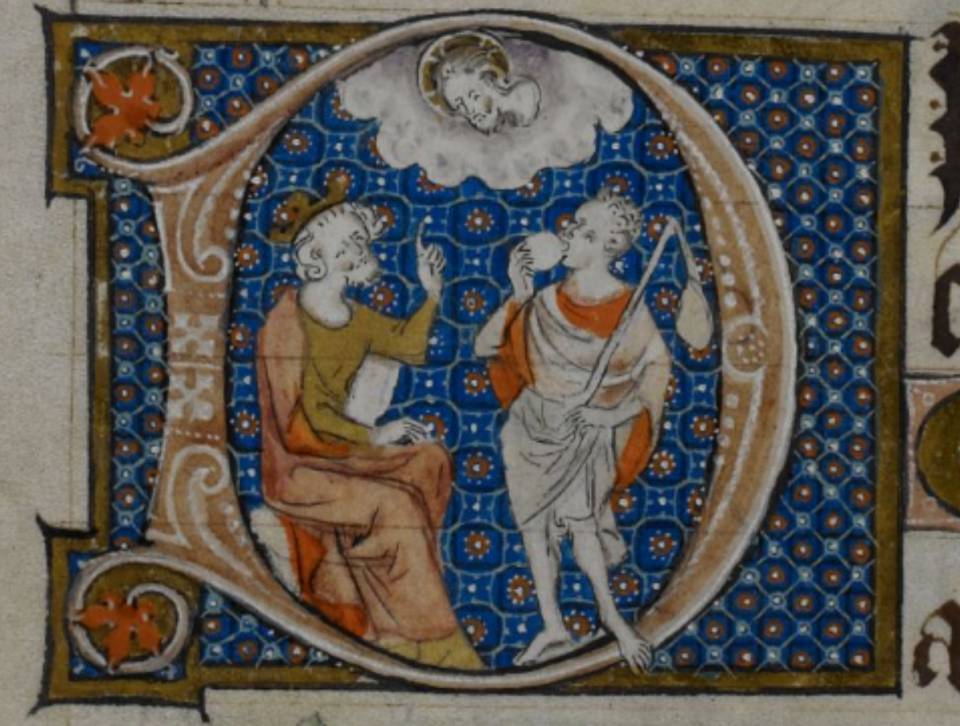

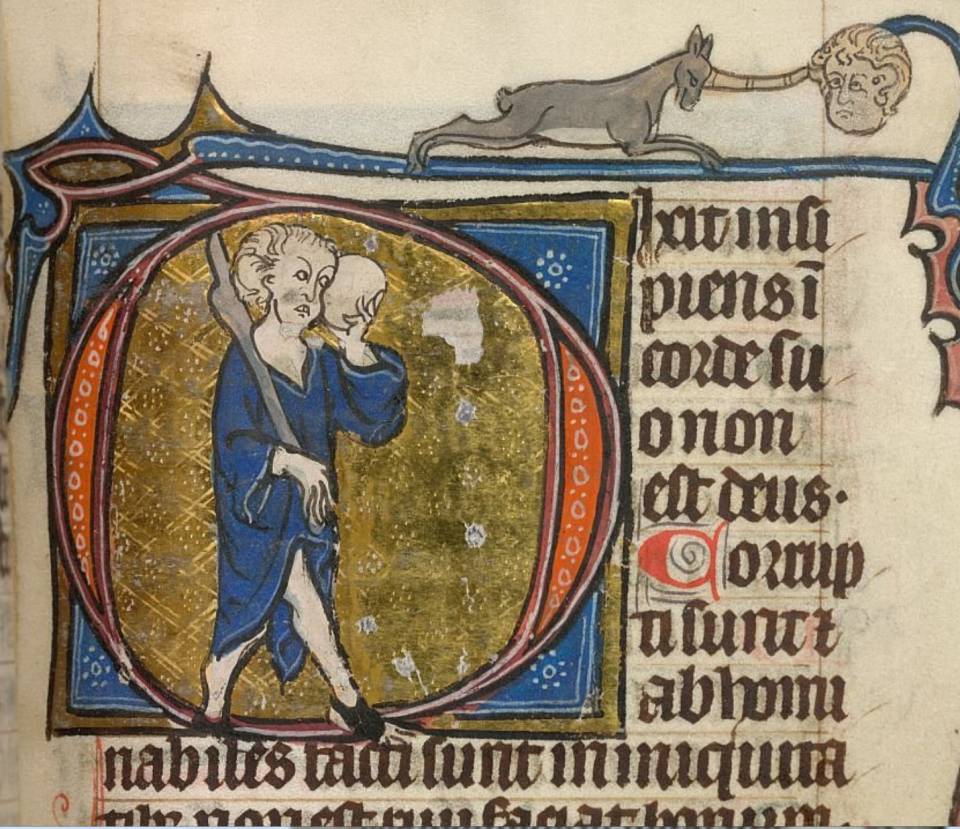

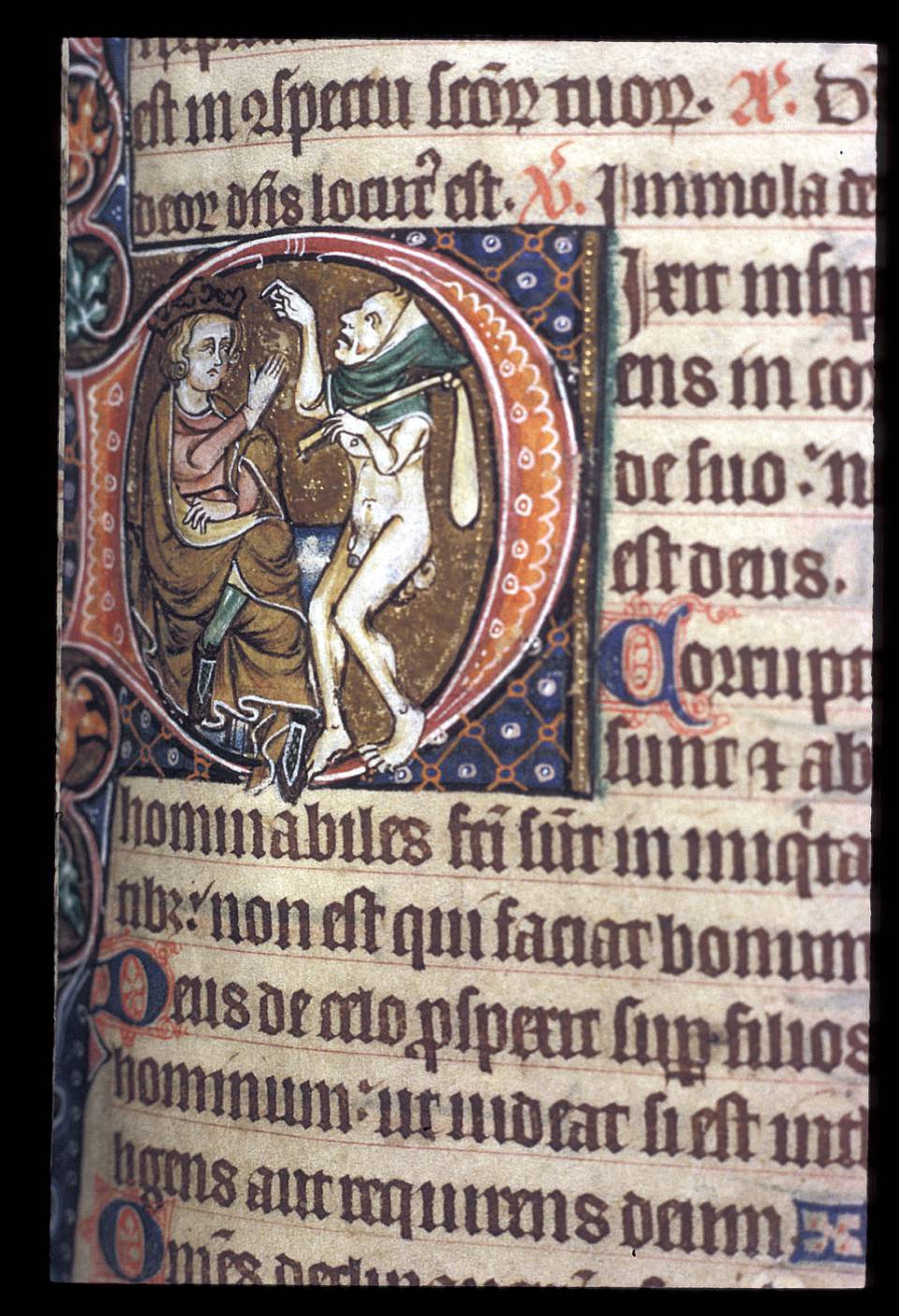

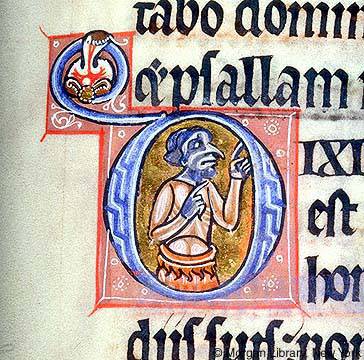

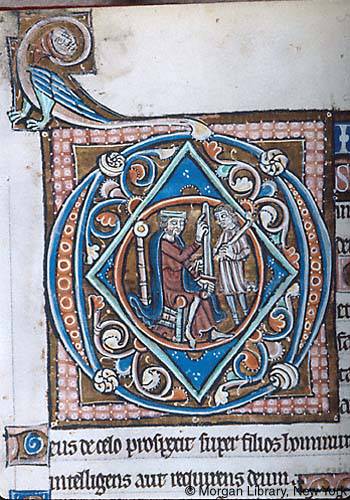

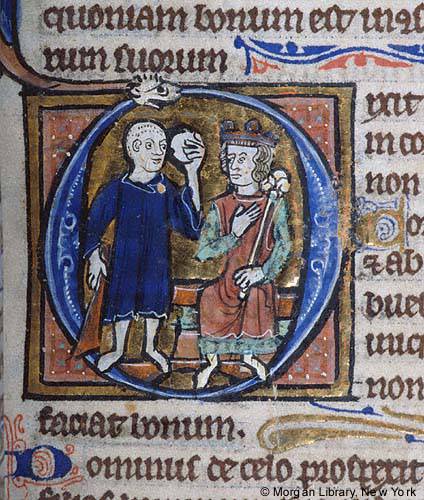

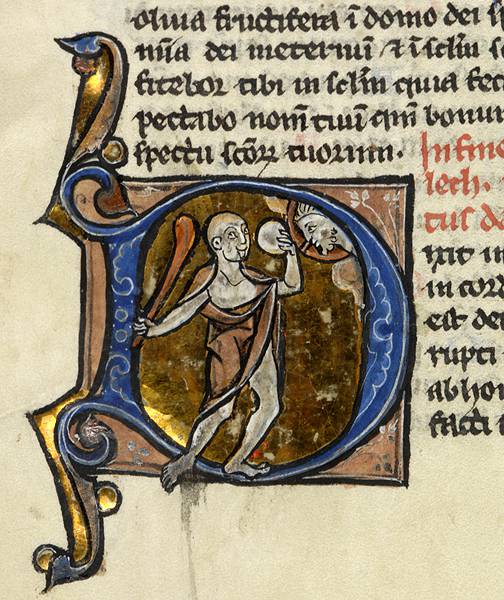

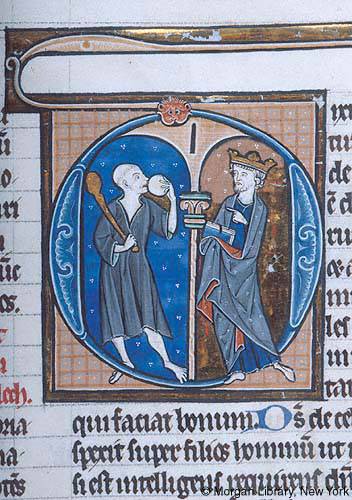

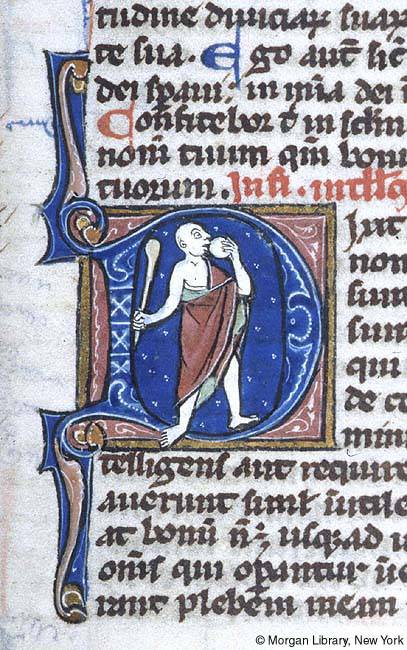

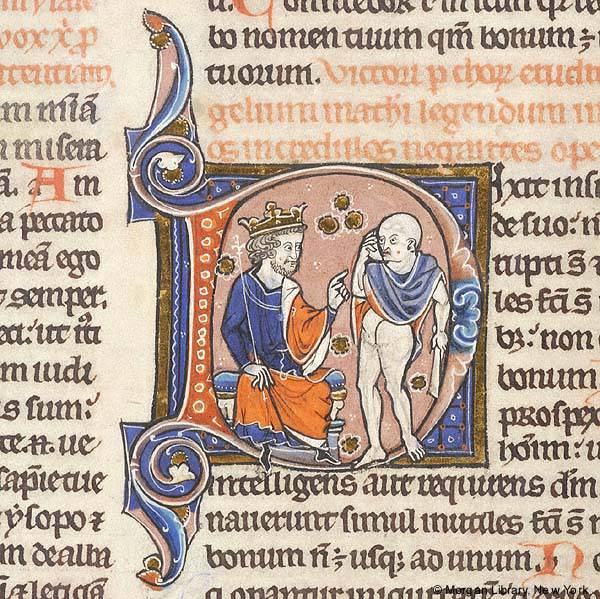

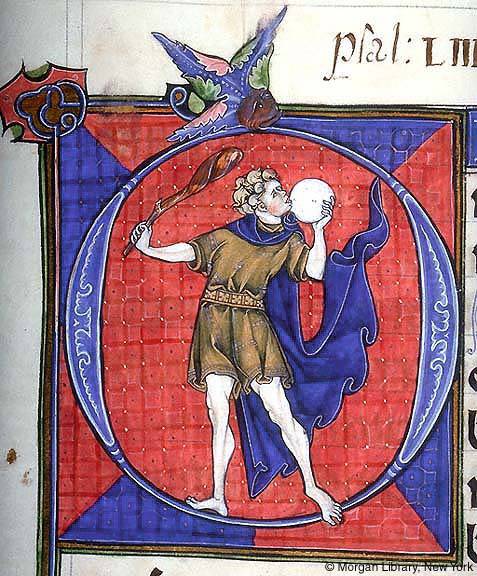

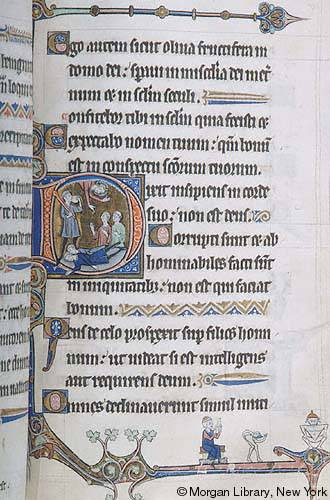

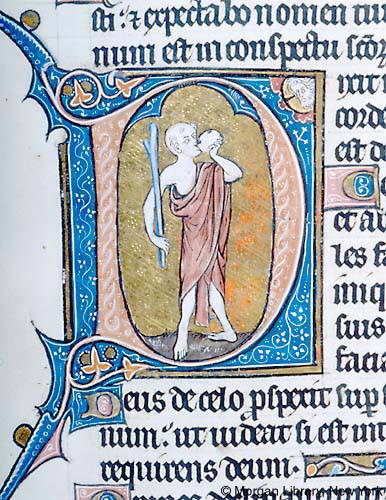

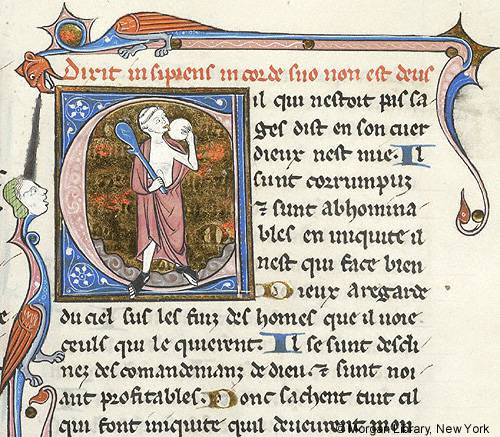

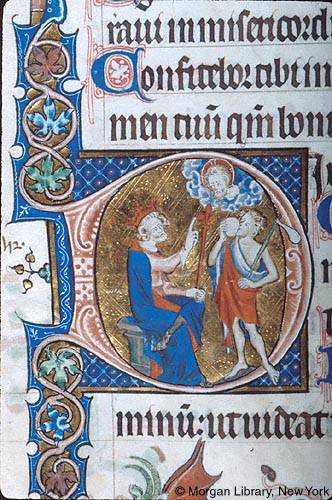

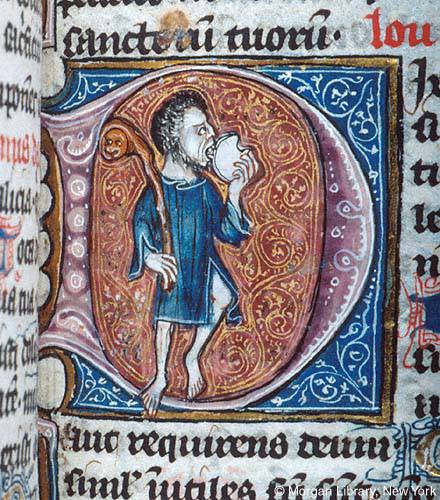

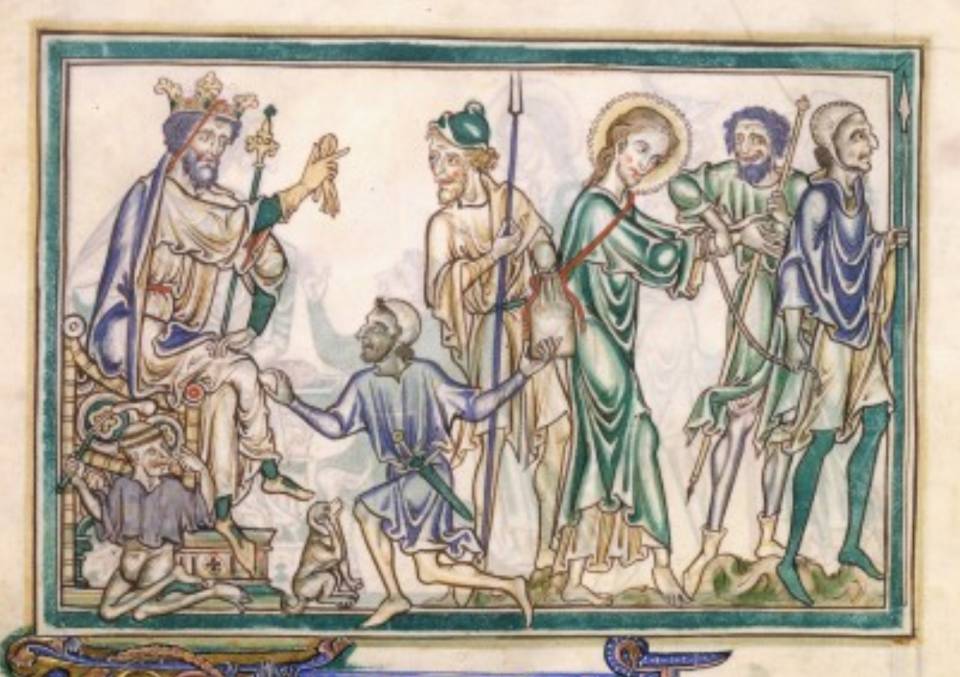

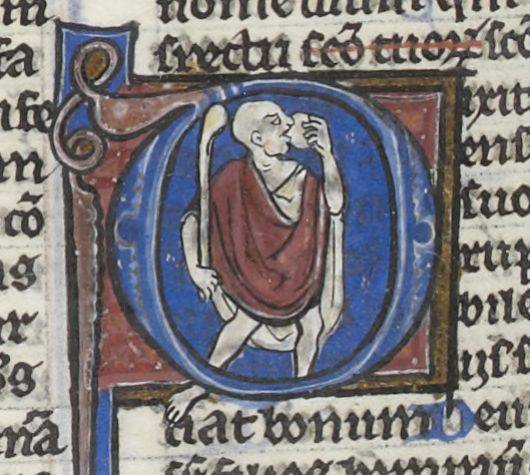

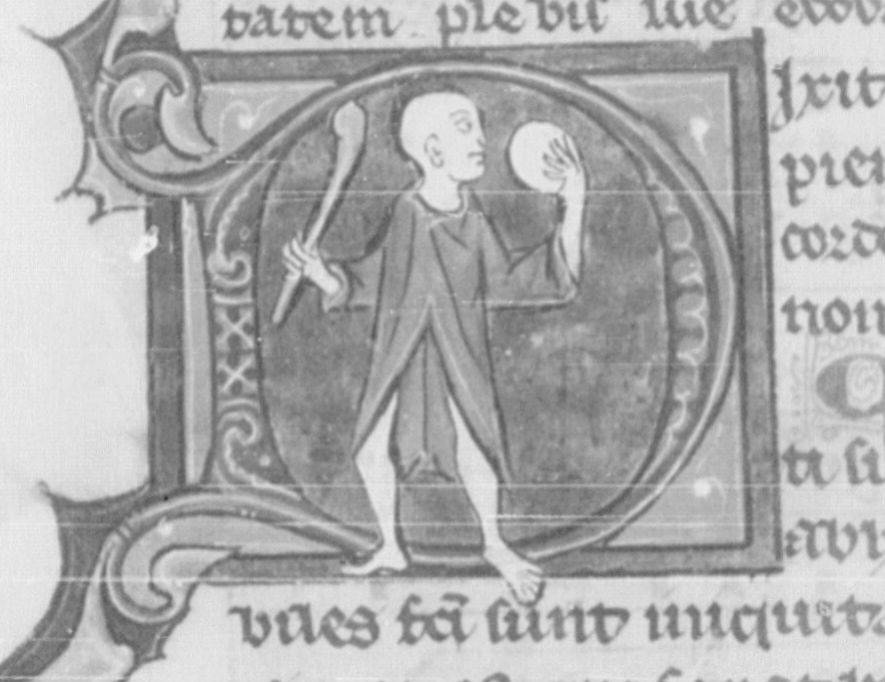

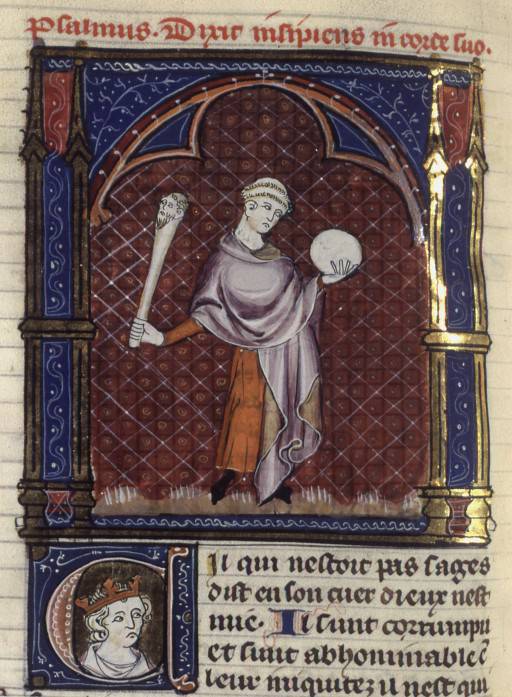

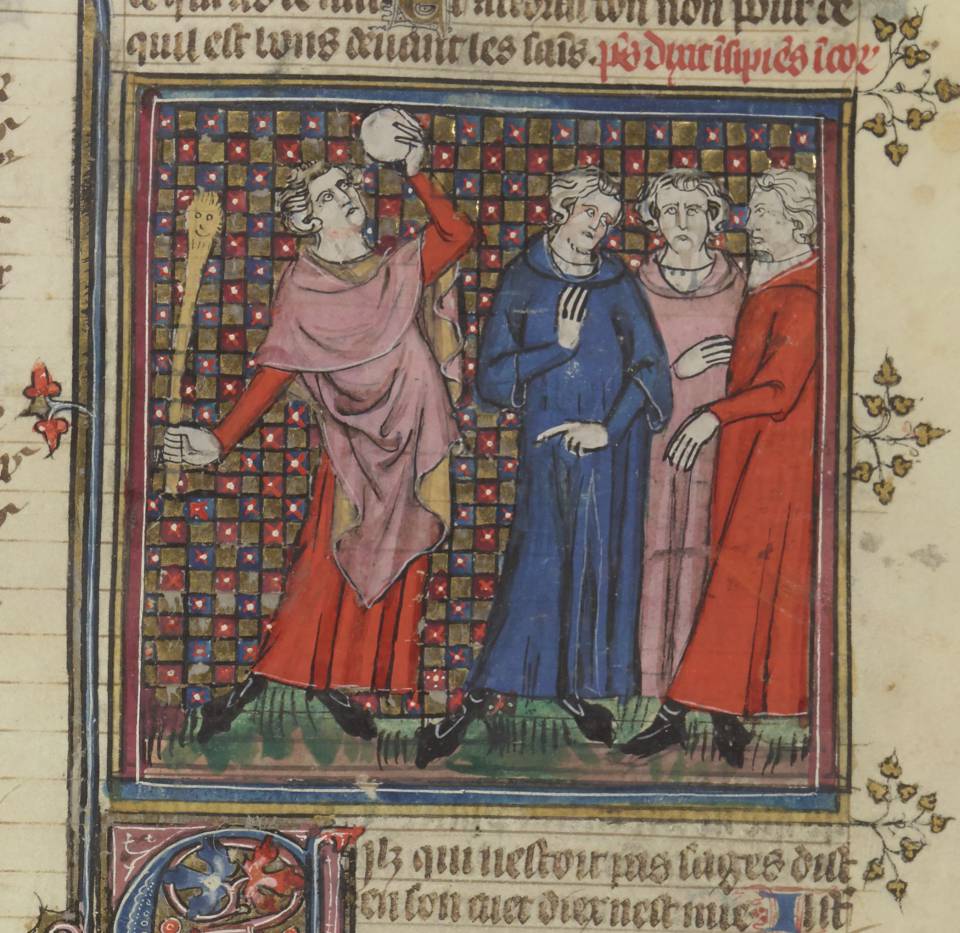

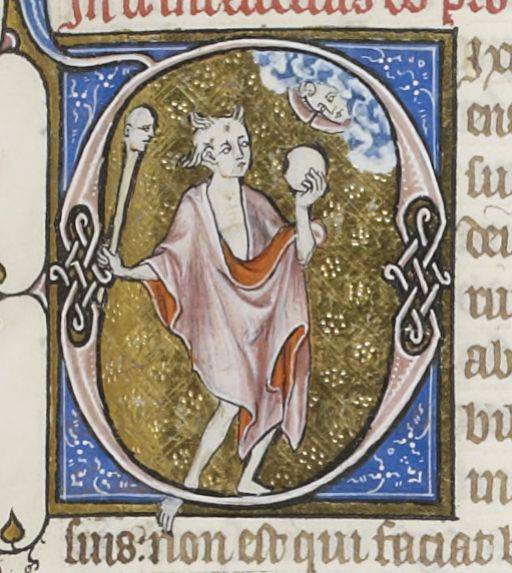

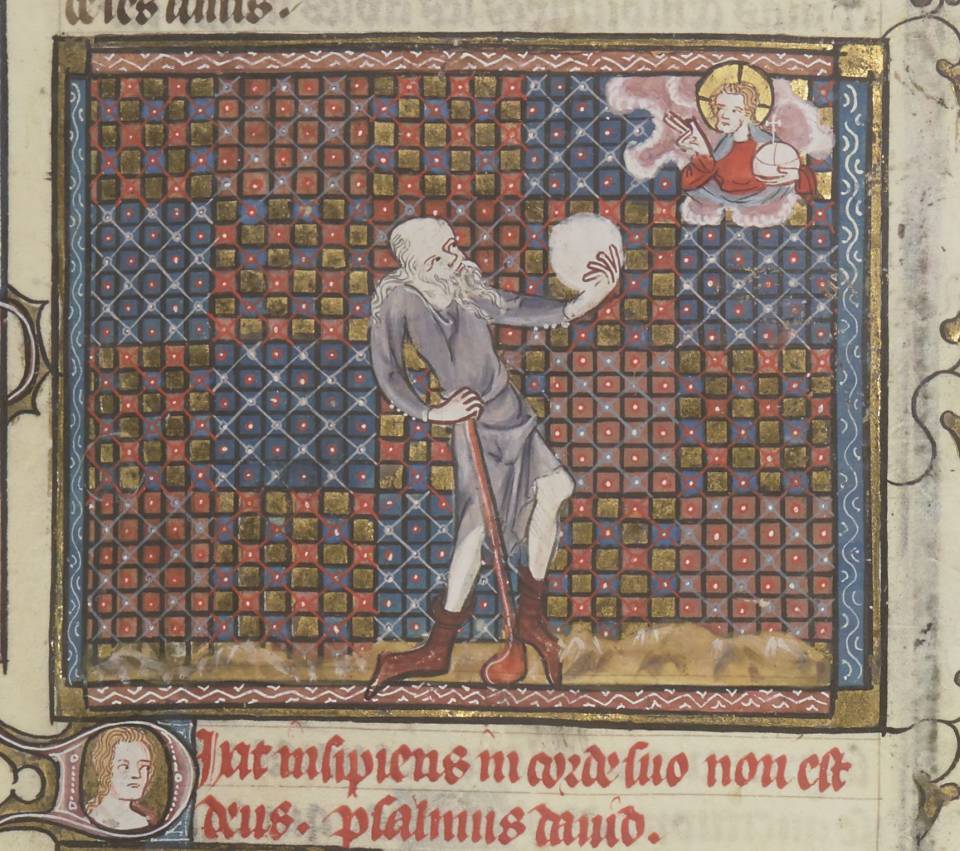

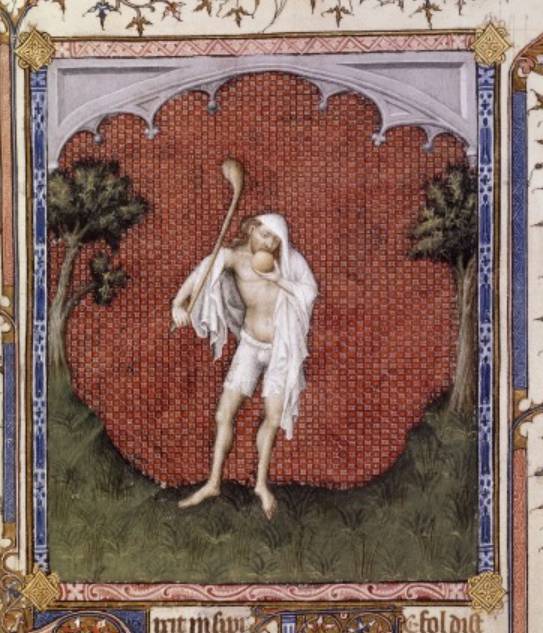

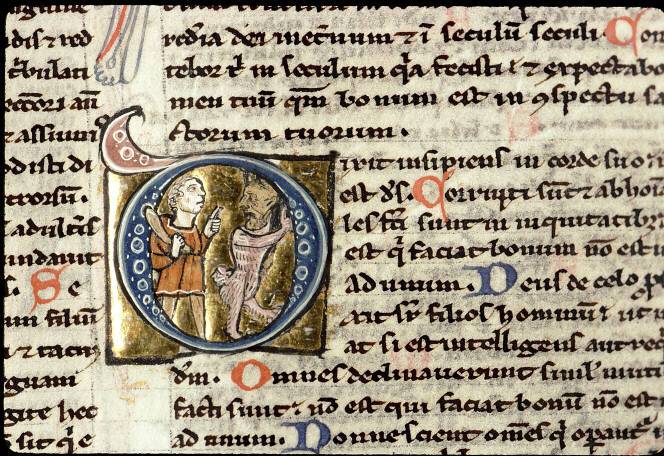

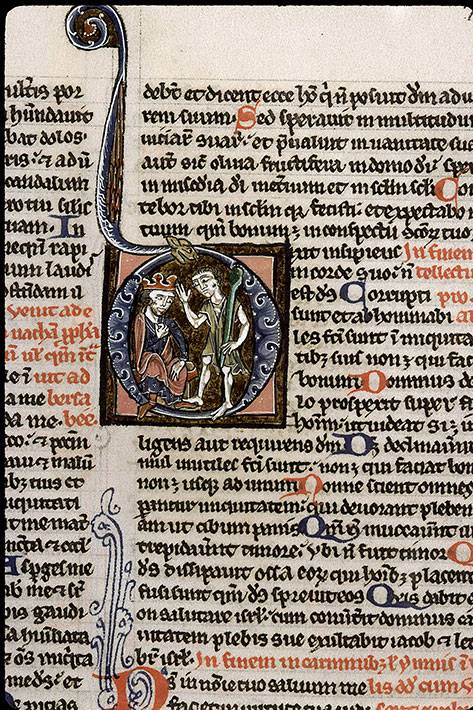

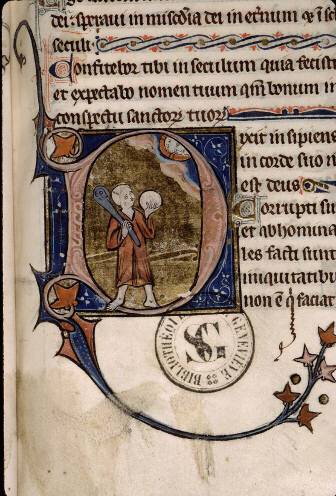

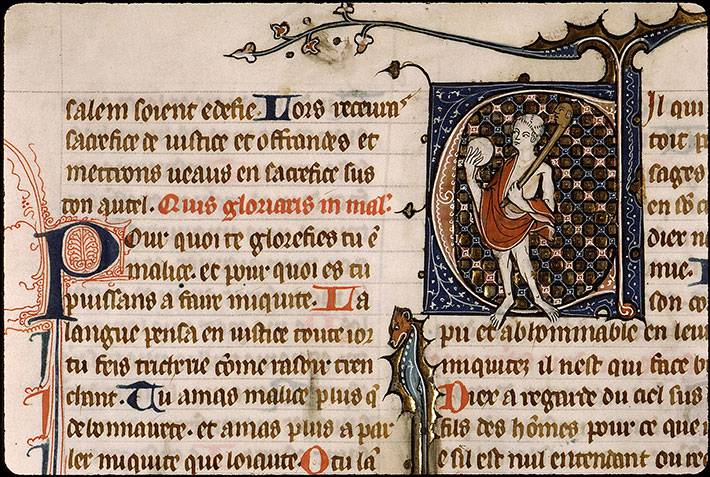

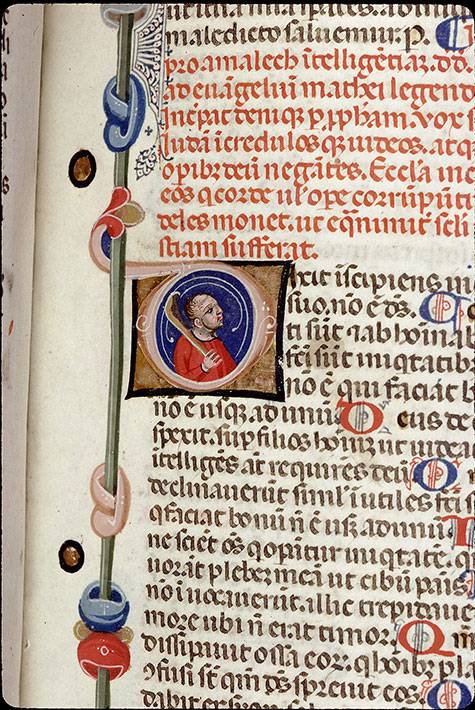

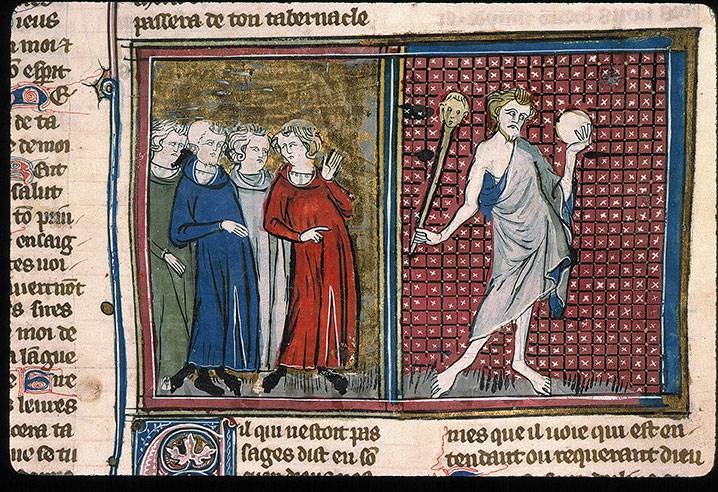

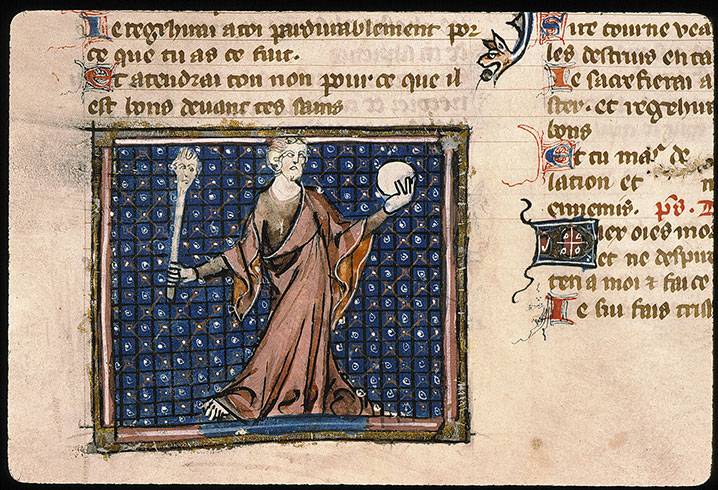

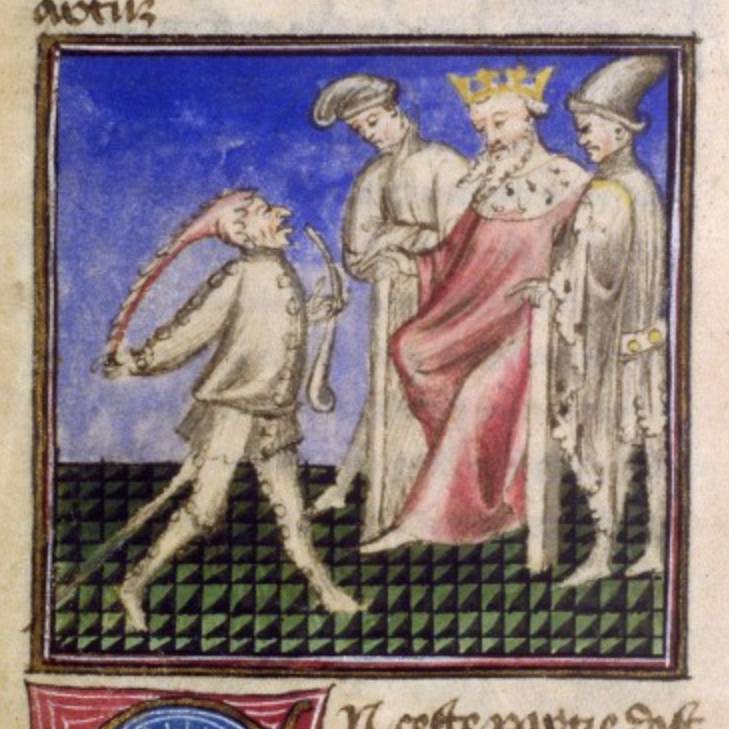

The fool is depicted in prayer books as an isolated dancer,28 either alone29 or in company of King David30, leg lifted, head askew, talking to his marotte, and often turning his back to the king in prayer. Miniaturists put special emphasis on the fool’s twisted body and motions, made to look even more extraordinary by colourful clothes and bells.31

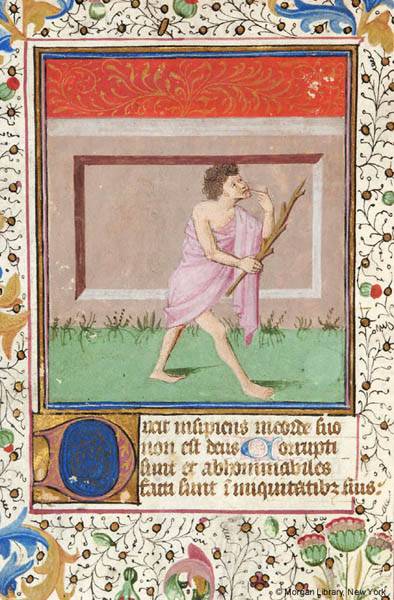

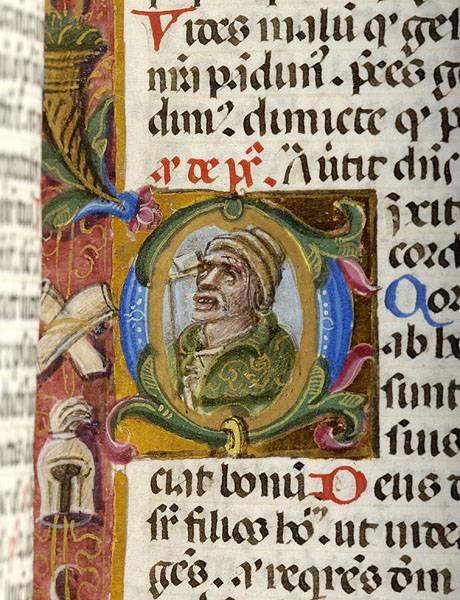

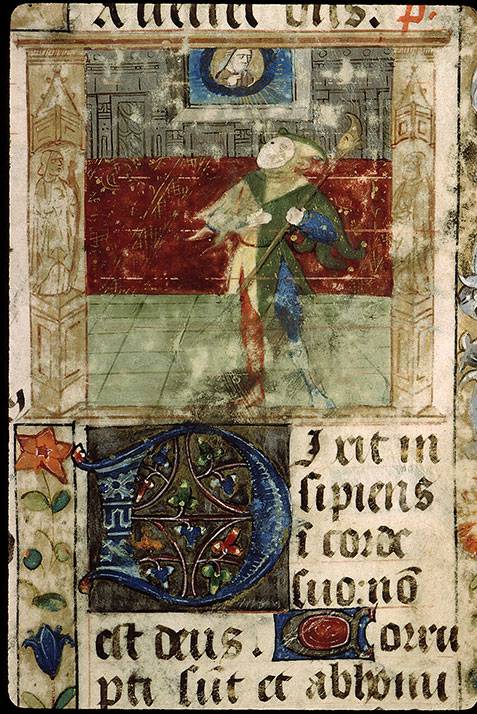

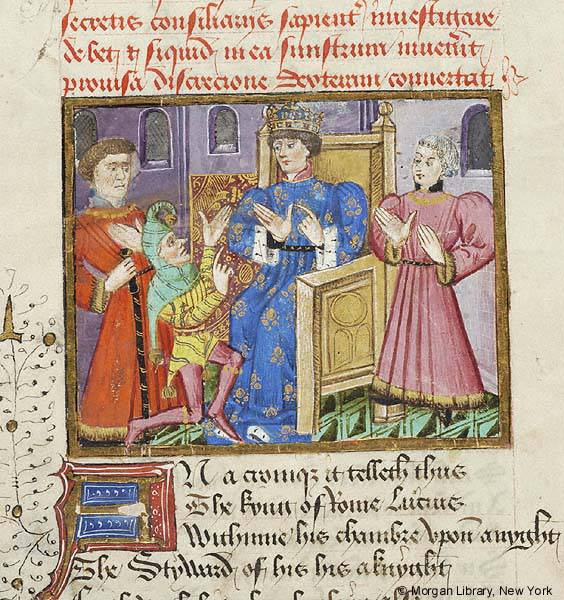

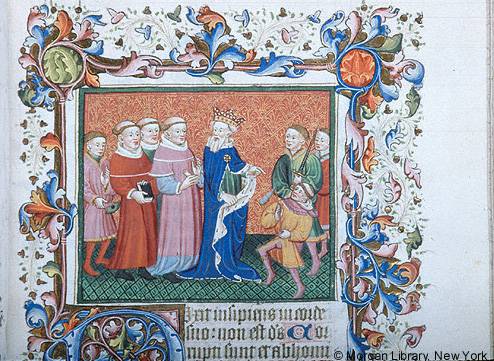

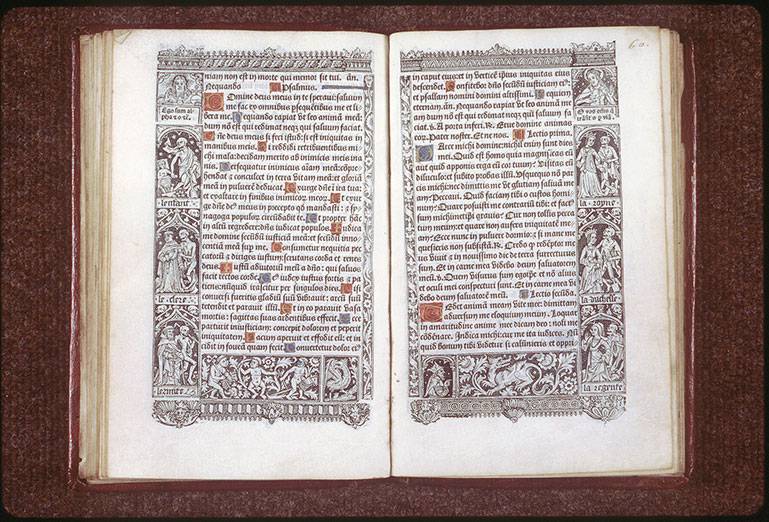

This type of dancing fool appears in prayer books, particularly in the opening words of Psalm 52, Dixit insipiens.32 Placed across from David, author of the Psalms and king of the Old Testament, the fool speaks blasphemous words right from the first verse. He is not represented for graphical or entertainment reasons, but rather for moral purposes. In the Breviary of John the Fearless33 the opposition between King David and the fool is underscored by the kneeling king, addressing prayers to God, and the hopping fool, dressed in red, blue, yellow, and white, talking to the phony head on his scepter. On one hand here is David praising God in his soul, on the other hand there is the fol oblivious to the presence of God in his heart.34 Likewise, in the Psalter of Charles VIII35 David dialogues in silence with God, dialogue suggested allegorically by a harp, while the fool speaks with his marotte, pointing his finger at the king. A chatty fellow, he commits in one streak the sins of loose talk and blasphemy: “The fool says in his heart, there is no God”.36 The verse’s meaning is not an ignorance of God, but a refusal of his existence in the fool’s heart. Thus the jumping fool represents sin and vice, whereas David embodies moral virtue.

At the same time, and once again within a religious context, the senseless creature’s gesticulations and jumping were sometimes established and approved by the Church, as in the case of the Feast of Fools.

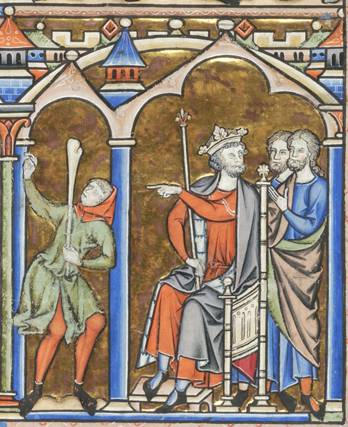

2) The dances of the Feast of Fools in churches

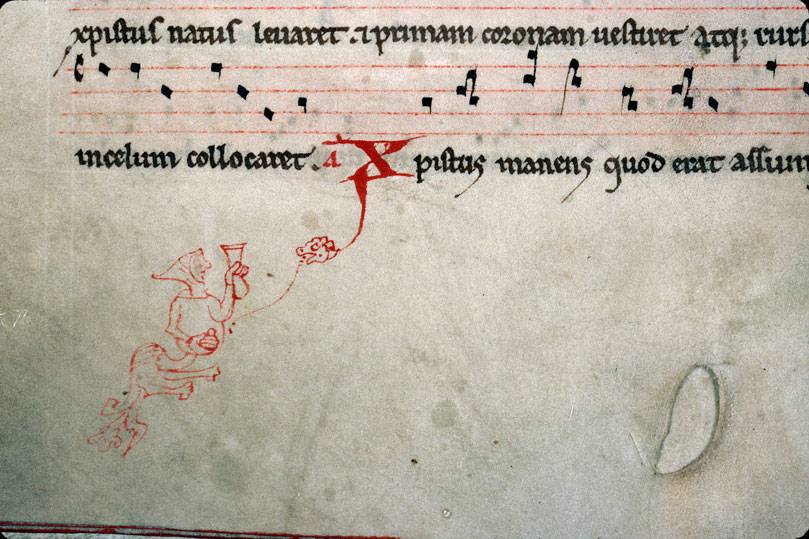

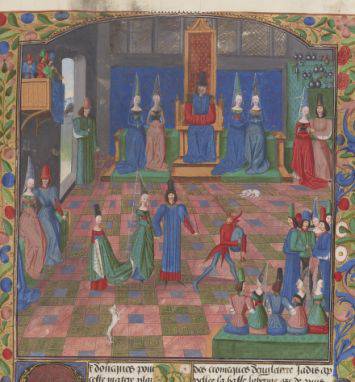

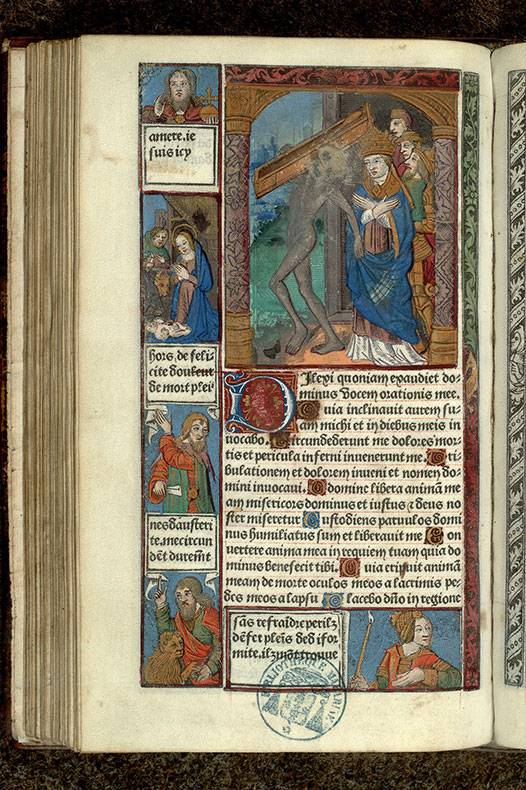

The Feast of Fool is ritual organised by the higher clergy of the cathedral and enacted by the lower clergy, namely the deacons, subdeacons, and choristers. Initially known as the Feast of the Circumcision or the Feast of the Ass between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, it became known as the Feast of Fools in the 15th century, when it spilled out of Church buildings into the streets in the form of Carnival celebrations.37 Taking place the day after the Nativity of Jesus, it was a celebration of childhood, St Stephen’s day (26 December), and marked the opening of festivities that lasted until the Circumcision (1 January) or the Epiphany (6 January) depending on the location.38 Youngsters and children were reversing the ecclesiastical hierarchy, parodying inside churches the bishop and the canons. The celebrations took the form of liturgical processions, dances, and conducti. Knowledge about the feasts is due in a good measure to the oldest manuscript with musical notation, containing the ritual of the Office of the Circumcision39 and attributed to the archbishop of Sens, Pierre de Corbeil (d. 1222), a member of the chapter of Notre-Dame.

The ritual may be summarised as follows.40 The feast began in the cathedral, where the choristers wore the canons’ copes and took their place in the stalls. At the vespers, the cantor performed the Magnificat: “Deposuit potentes de sede”, “He hath put down the mighty from their seat: and hath exalted the humble and meek. He hath filled the hungry with good things: and the rich he hath sent empty away.” Then the children elected a bishop and gave him a miter, a cape, gloves, and other bishop’s accessories, after which he received the crozier, was put on the episcopal throne, and everybody bowed in front of him as if before a real bishop. He offered a banquet and wine. All night long, the feast alternated between vigils, songs, dances, and processions. The Beauvais Office also notes that the mock bishop proceeded down the nave mounted on an ass.41

The donkey was led to the altar to the chanting of a conductus ad tabulam, and the cantor performed the Office of the Ass.42 He began with a joyful song, “Away from here all that is sad!” and introduced the “Prose of the Ass”, Orientis partibus, the opening words of which are the joyful formulas “In januis ecclesiae / Lux hodie, lux laeticie” “This day is a day of joy [...] Those who celebrate the Feast of the Ass want only joyfulness.” 43 The Prose of the Ass was followed by other elements of the Christmas cycle, according to the time of day or night. A reading of the Office does not in itself reveal anything scandalous. However, the joyous imitations of the donkey in vernacular language "Hez! sir asne hez! Hez", the recurrence of verbs and expressions signifying joy - gaudere, exultare, jubilare, felix - as well as conducti dedicated to play,44 drinking,45 and meals,46 represent an indulgent celebration of the time of the Eucharist within a joyful mundus inversus. With its focus on the ass and the children, this ritual of inversion was an exaltation of poverty of spirit, innocence, and sacred folly. It had its basis in the parables of the Gospel of Luke, where children and the poor47 were elevated to the ranks of the powerful in the kingdom of God.48

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Church’s position on the Feast of Fools was ambiguous, given that the church condemned its excesses — to little avail —, but did not really prohibit them. In the twelfth century the Feast is tolerated, as illustrated by Odo, Bishop of Paris, who reformed it rather than abolishing it.49 Some clerics at Notre-Dame wrote musical pieces particular to this celebration, such as a certain Pérotin, who wrote a conductus for three voices, Salvatoris hodie.50 Then the condemnation became gradually firmer: in 1198, the Papal Legate Peter of Capua wrote to the same Odo, Bishop of Paris, to deplore the “enormitas”, “pollution of words”, and bloodshed;51 in 1210, Pope Innocent III (1160-1216) denounced these practices as unworthy of members of the clergy;52 the council of Paris in 1212 renewed the ban forbidding archbishops or bishops from tolerating or, worse, supporting this type of ritual; in 1435, the council of Basel condemned the Feast of Fools.

Despite such condemnations, the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, decided to maintain the feast and had the charter for the Privilege of Fools drawn up at his chapel, in which he asked the fools to make “good and marry” feast, “without fail”.53 There is perhaps a correlation between the depiction of the “bishop of fools” in the Bible of Nicolas Rolin (c. 1450), chancellor to Philip the Good, and the institution of the Feast of Fools in the ducal chapel on the same date in 1454. At the same time, a fools’ bishop was featured in the Bible of Nicolas Rolin, the chancellor of the Duke. Covered with bells, he is topped with a pair of bellows on his head pointed the word “wisdom” (sapientiam) in the Proverbs of Solomon. This “pair of bellows” could correspond to the definition of “fool” - "fol" in ancient French, which means a “bag full of air”, in other words an “empty head” filled with air. This page may be interpreted as a mirror of madness and wisdom for the chancellor of the Duke.

Further, the same year saw the creation in Dijon, Burgundy of the “Company of Mère Folle” and with it the carnivalesque and satirical Feast of Mère Folle. This Feast was celebrated by about five hundred “fellows” of “each and every quality”. Her members dressed in disguise danced in the city and performed satirical acts on carts during Carnival. The headdress of the “Mère Folle” was yellow and green with bells — it is now preserved in the Musée de la Vie Bourguignonne in Dijon. Her banner features two fools who are jumping around while standing head to tail and farting (pétant au nez) in each other’s faces. For so behaving, they were nicknamed Pétengueules.54

By means of inversion, foolish feasts consolidated the social order. In their own way, rich manuscripts represented this order by depicting dancing fools.

III. Fools in courtly dances: the farandole and the morisque

1) Farandoles and disguises

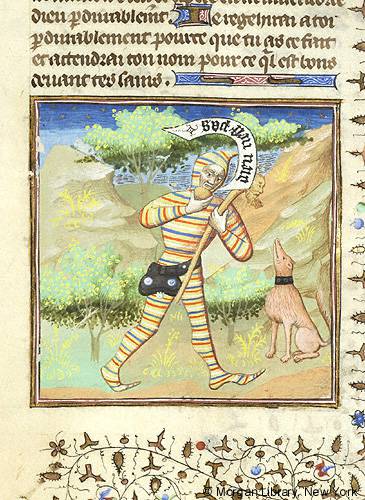

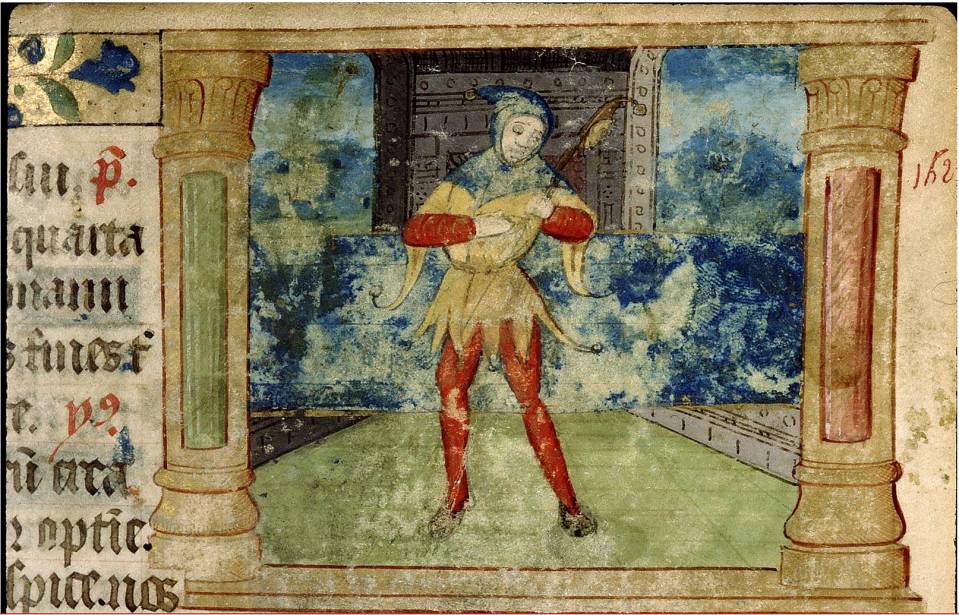

Representations of dancing fools can also be found in secular, royal, and princely books, such as the Roman d’Alexandre (Romance of Alexander).55 This precious manuscript was illuminated in Bruges in the 1340s, to be offered by Queen Philippa of Hainault as a gift to King Edward III of England (1327-1377).56Almost all the pages are decorated with margins of dancing fools, jugglers, costumed characters, monkeys, and singing birds. For example, folio 84 v° depicts two fools playing the portative organ and bagpipes, and five dancers disguised as fools and wearing bichromatic headdresses (red and blue, or pink and red) fitted with bells. They all form an “impossible” farandole, moving, twisting, turning, and jumping in opposite directions. Their disguises and dances are a reference to the celebrations of the Carnival.

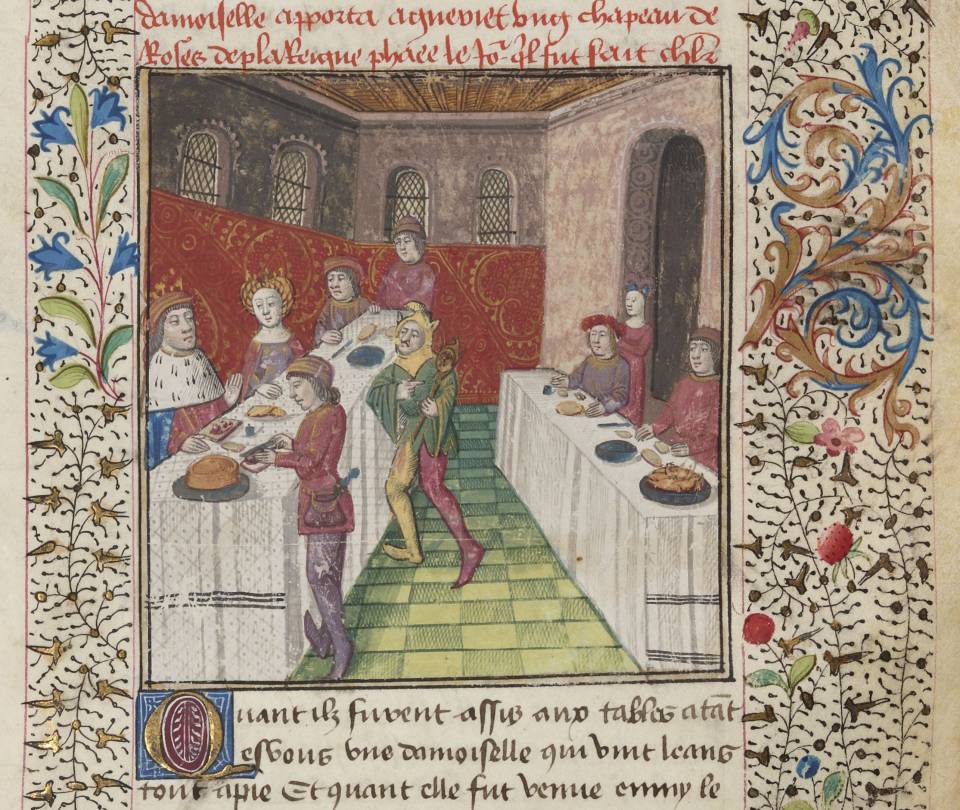

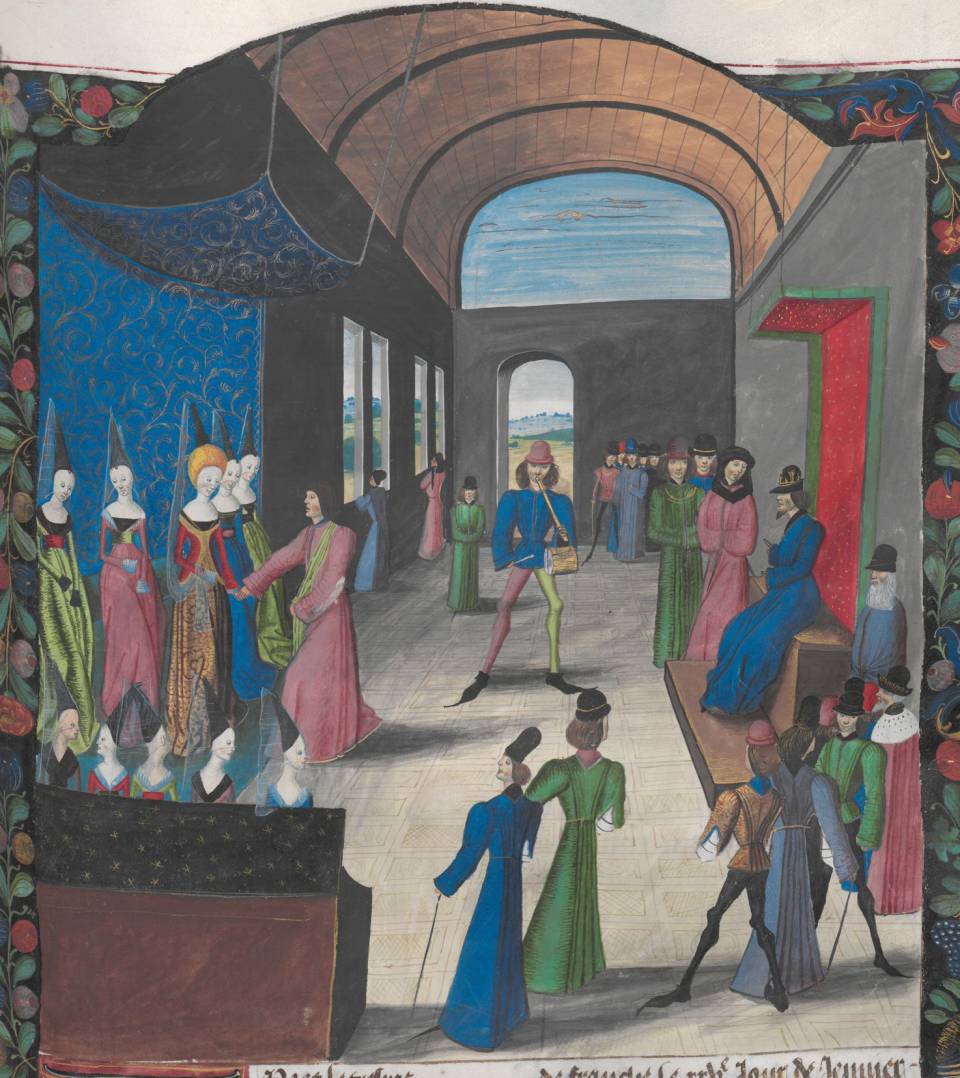

Home to renowned festivities, the court of Edward III57 was attended by a great number of fools, as well as minstrels, jugglers and animals. The feasts, like those held at the Burgundian court in the fifteenth century,58 also feature a fool playing music (the bagpipes), dancing and making the court dance, as shown in the miniature of The Chronicles of France and England by Jean of Warvin. One of these “foolish dances” is the morisque, and can be found in some of the religious and secular manuscripts that belonged to the nobility.

2) The fools’ morisque

The morisque is represented in courtly manuscripts. It is featured in the illuminations of the manuscripts of The City of God by Augustine of Hippo, a copy of which is kept in The Hague.59 The images depict fools from both genders dancing naked to the sound of jingle bells and tambourines;60 they are associated with the idolatry and paganism that Augustine’s text condemns. The quickness of their steps is reminiscent of the “moresca”.61 As the name suggests, this is a fast-paced Moorish dance that was popular in the European courts of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. There are references to the oriental origins of the dance in works such as Book of the Marvels of the World,62 a chronicle of the Italian merchant Marco Polo’s travels across Asia. The workshop of the Boucicaut Master completed the task of illumination for John the Fearless, who offered it to his uncle, John, Duke of Berry, in January 1413. All the musicians and dancers depicted in this manuscript look like minstrels or court jesters, but they are dressed with oriental turbans, colourful mid-part scarves, and bells.

In fact, the accounts of the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, mention the employment at the royal court of a morisque dancer by the name of Estevenin Paresis,63 and the Duke likely employed other dancers. Moreover, these accounts show the similarities between the costumes of morisque dancers and those worn by court jesters: they are colourful, cut in luxurious material and decorated with bells and jingle bells. For example, in 1428, Hue de Boulogne, Philip the Good’s painter and valet, received an order for “seven pieces of draping clothes made out of colourful silk and put together in a strange fashion, suitable for morisque dances and embellished with gold and silver Brazil skin, along with a pair of canvas hose made out of snakeheads streaked with gold, shoes and bells for all costumes used in morisque dances”.64

Did the agility and flexibility required by the morisque, together with its oriental origins, contribute to the perception that it was a fool’s dance? If so, this could explain why illuminators included fools in the representations of the dance, both in religious and secular manuscripts.

However, fools’ dances are not all quite as joyous, as shown by the danse macabre in the late medieval era.

IV. The dance of death, a reflection of the living and society

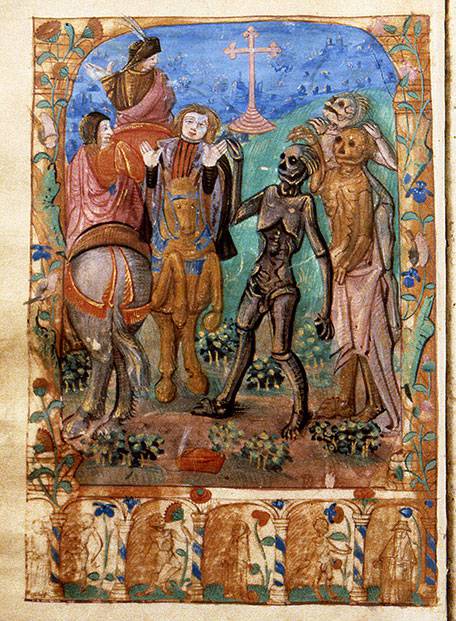

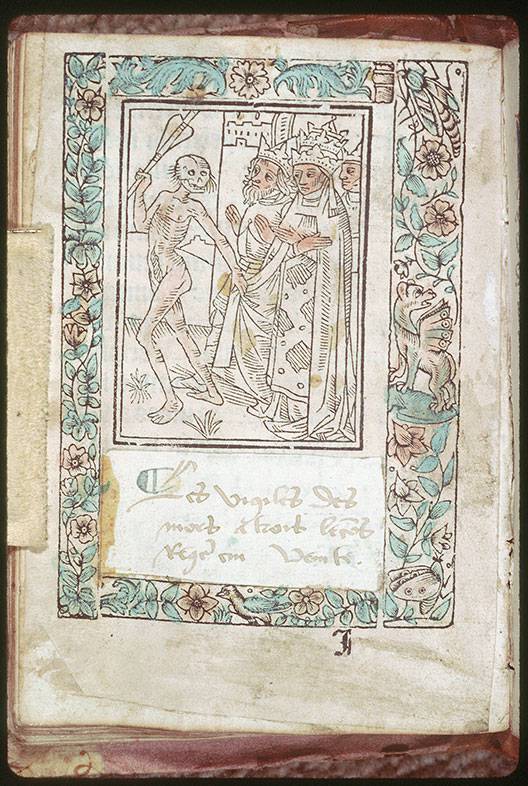

The frequency of representations of the danse macabre increases in Europe in the fifteenth century, particularly in murals, illuminated manuscripts and printed books (incunabula, if printed up to the year 1500).65 The origins of these representations can be traced back to The Three Living and the Three Dead66(a copy of which can be found in the Psalter of Robert De Lisle).67 The depiction of the danse macabre alternates between a living and a dead character, the two holding hands. They are represented by a farandole ordered according to the social hierarchy: the first living its double are the pope, then the emperor, the king, the prince, the cardinal, etc., to the plowman, and the child. Skeletons symbolise the living when they die, their doubles of sorts.

Following the rhythm of the music produced by the skeletons, the danse macabre is presented either in the form of a farandole, more precisely a trepidum,68 or as an ensemble of dancing pairs, each containing a dead and a “bright” character. The dead usually play the bagpipes, the organ, the harp, the trumpet and the tambourine. They either stand in front of the dance and at a certain distance from it (as seen at the Abbey in La Chaise-Dieu or at St. Mary’s Church in Berlin), or they lead the dance (as seen at the Church of St. Germain in La Ferté-Loupière, Burgundy). On the basis of the instruments they play, the dead are believed to be a reference to psychopomps, such as sirens, the guides of souls into the afterlife.

Dressed in a costume with bells, the fol is part of the farandole. He goes under the name of le sot and is present in the incunabula of La Danse macabre (The Dance of Death) by Guyot Marchant69 and Antoine Vérard.70 He dances in the farandole because, like the king and the bishop, he is a member of society. However, the humanistic themes in vogue at the time most likely account for his presence. Indeed, poets such as Charles of Orléans and François Villon deplored the foolishness of humanity, the melancholy of time, the fleeting nature of life, and the fear of death. In the danse macabre, the sot engages in the farandole of a life that leads inexorably towards death. He prefigures the fool who, in The Praise of Folly of Erasmus (1511), speaks his truth to everyone,71 denounces the tragedy of the world’s madness and calls for the moral consciousness of humans.72

Conclusion

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the images of “dancing fools” feature a variety of dances and fools: the senseless creature in the Dixit insipiens of Psalm 52, the fools' bishop officiating at the Feast of Fools, the dancers of Carnival, the morisque dancer, and the sot in the danse macabre. The visual forms do vary. Nonetheless there are common and vivid models and themes in the images, in the context of significant political, religious and social turmoil. They always relate to the inversion of social and religious hierarchies, and to the concomitant tensions and oscillations between piety and impiety, order and disorder, laughter and the macabre, life and death.

1 Francastel, Pierre: La figure et le lieu. L’ordre visuel du Quattrocento, Paris 1967.

2 Clouzot, Martine: Musique, folie et nature au Moyen Âge. Les figurations du fou musicien dans les manuscrits enluminés (XIIIe - XVe siècles), Bern 2014, 500 p., 13 ill.

3 Guerreau-Jalabert, Anita: La culture ecclésiastique, in: Sot, Michel; Boudet, Jean-Patrice; Guerreau-Jalabert, Anita: Histoire culturelle de la France, Paris 1997, p. 143-179, ici p. 146.

4 Guerreau-Jalabert, Anita: La culture ecclésiastique, in: Sot, Michel; Boudet, Jean-Patrice; Guerreau-Jalabert, Anita: Histoire culturelle de la France, Paris 1997, p. 146.

5 Cf. Lever, Maurice: Le sceptre et la marotte. Histoire des fous de cour, Paris 1983.; Koopmans, Jelle: Le théâtre des exclus au Moyen Age. Hérétiques, sorcières et marginaux, Paris 1997.; Southworth, John: Fools and jesters at the English court, Stroud 1998.; Mezger, Werner; Götz, Irene: Narren, Schellen und Marotten. Elf Beitr. zur Narrenidee, Remscheid 1984 (Kulturgeschichtliche Forschungen).; Perry, Lucy: Behaving like fools. Voice, gesture and laughter in texts, manuscripts and early books, Turnhout 2011.

6 Heers, Jacques: Fêtes des fous et carnavals, Paris 1983.

7 Jacquart, Danielle: La réflexion médiévale et l’apport arabe, in: Bancaud, Jean; Quétel, Claude; Postel, Jacques (Hg.): Nouvelle histoire de la psychiatrie, Toulouse 1983, p. 43-53.

8 Laharie, Muriel: Images de la folie au Moyen Âge (XIIe-XVe siècle), in: Marie-Laverrou, Florence (Hg.): Le fou, cet autre, mon frère : littérature, civilisation et linguistique, Paris 2012., p. 19-34.

9 Fritz, Jean-Marie: Le discours du fou au Moyen Age. Etude comparée des discours littéraire, médical, juridique et théologie de la folie, Paris 1992.

10 Harris, Max: Sacred folly. A new history of the Feast of Fools, New York 2011.

11 Dull, Olga Anna: Folie et rhétorique dans la sottie, Genève 1994.

12 Foucault, Michel: Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique, Paris 1972 (1961).

13 Cf. Brucker, Charles: Sage et sagesse au Moyen Age (XIIe et XIIIe siècles). Étude historique, sémantique et stylistique, Genève 1987, p. 32-33.

14 Cf. Fritz, Jean-Marie: Le discours du fou au Moyen Age. Etude comparée des discours littéraire, médical, juridique et théologie de la folie, Paris 1992, p. 1-12.

15 Fritz, Jean-Marie: Le discours du fou au Moyen Age. Etude comparée des discours littéraire, médical, juridique et théologie de la folie, Paris 1992, p. 7-9.

16 Cf. Saward, John; Tadié, Marie: Dieu à la folie. Histoire des saints fous pour le Christ, Paris 1983, traduit de l’anglais par Marie Tadié, titre original: Perfects Fools: Folly for Christ’s sake in catholic and orthodox spirituality, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1980.

17 Marbode, Patrologie latine, 171, col. 1483, cité dans Dalarun, Jacques: Robert d’Arbrissel, fondateur de Fontevraud, Paris 1986, p. 56-57.

18 Cf. Nattiez, Jean-Jacques: Histoires des musiques européennes, Bd. 4, Arles 2006 (Musiques. Une encyclopédie pour le XXIe siècle).

19 Cf. Bell, Nicolas: Music in medieval manuscripts, London 2001.

20 Eco, Umberto: Le problème esthétique chez Thomas d’Aquin, Paris 1993 (1970), p. 88-89 et Eco, Umberto: Les esthétiques de la proportion, in: Art et beauté dans l’esthétique médiévale, Paris 1997(1987), S. 55–75.

21 Malhomme, Florence; Wersinger, Anne-Gabrielle: Mousikè et aretè. La musique et l’éthique, de l’Antiquité à l’âge moderne, Paris 2007, p. 8.

22 Platon: La république. Livre III, Platon oeuvres complètes, <http://remacle.org/bloodwolf/philosophes/platon/rep3.htm>, Stand: 19.04.2017, 396c-405d.

23 Cf. Eco, Umberto: Le problème esthétique chez Thomas d’Aquin, Paris 1993 (1970), p. 88-89 and Eco, Umberto: Art et Beauté dans l’esthétique médiévale, Paris 1997 (1987), p. 55-75.

24 Cf. Dull, Olga Anna: Folie et rhétorique dans la sottie, Genève 1994.

25 Quintilianus, Marcus Fabius: Institutes of Oratory, Book 8, Chapter 6, Rhetoric and Composition, <http://rhetoric.eserver.org/quintilian/8/chapter6.html>, Stand: 19.04.2017, 44.

26 Boltanski, Luc; Thévenot, Laurent: De la justification. Economie des formes de grandeur, Paris 1991.

27 Cf. Mullally, Robert: The Carole. A study of a medieval dance Ashgate, 2011; Schmitt, Jean-Claude: Les rythmes au Moyen Âge Paris 2016.

28 Wirth, Jean, avec la collaboration d'Isabelle Engammare et des contributions d’Andrea Braem, Herman Braet, Frédéric Elsig, Isabelle Engammare, Adriana Fisch Hartley, Céline Fressart, Les marges à drôleries dans les manuscrits gothiques (1250-1350), Genève 2008 (Matériaux pour l'Histoire publiés par L'Ecole des Chartes, 7).

29 Bruxelles, Bibliothèque Royale, ms. 9511, f. 387 v°, Breviary of Philip the Good, c. 1450.

30 Clouzot, Martine: Le fou et le livre: des exemples pour le roi. Le fou du roi et son iconographie (XIIIe-XVe siècle), in: Toussaint, Jacques (Hg.): Pulsion(s). Images de la folie du Moyen Âge au siècle des lumières, Namur 2012. p. 39-72.

31 Menard, Philippe: Les emblèmes de la folie dans la littérature et dans l’art (XIIe-XIIIe siècles), in: Backès, Jean-Louis; Payen, Jean-Charles (Hg.): Hommage à Jean-Charles Payen. Farai chansoneta novele, Caen 1989.; Gross, Angelika; Thibault-Schaefer, Jacqueline: Tristan, Robert le Diable und die Ikonographie des Insipiens, in: Buschinger, Danielle; Spiewok, Wolfgang (Hg.): Schelme und Narren in den Literaturen des Mittelalters: XXVII. Jahrestagung des Arbeitskreises Deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters, Greifswald 1994, p. 55-73.

32 Cf. Langenfeld, Dagmar; Götz, Irene: Nos stulti nudi sumus - Wir Narren sind nackt. Die Entwicklung des Standard-Narrentyps und seiner Attribute nach Psalterillustrationen des 12. bis 15. Jahrhunderts, in: Mezger, Werner; Götz, Irene (Hg.): Narren, Schellen und Marotten. Elf Beitr. zur Narrenidee, Remscheid 1984 (Kulturgeschichtliche Forschungen 3), S. 37–96.

33 Breviary of John the Fearless and Margaret of Bavaria, London 1413-1419, British Library, The Harley Collection, Signatur: Harley 2897.

34 From Proverbs 10, 19, St. Augustinus wrote in the De Trinitate: “in the abundance of words, you shall not escape out of the sin”.

35 Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. lat. 774, f. 63 v°, Psalter of Charles VIII, end of 15th c.

36 Cf. Langenfeld, Dagmar; Götz, Irene: Nos stulti nudi sumus - Wir Narren sind nackt. Die Entwicklung des Standard-Narrentyps und seiner Attribute nach Psalterillustrationen des 12. bis 15. Jahrhunderts, in: Mezger, Werner; Götz, Irene (Hg.): Narren, Schellen und Marotten. Elf Beitr. zur Narrenidee, Remscheid 1984 (Kulturgeschichtliche Forschungen 3), S. 37–96.

37 Fabre, Daniel: Carnaval, ou la fête à l’envers, Paris 1992.

38 Cf. Heers, Jacques: Fêtes des fous et carnavals, Paris 1983, p.105-189. Southworth, John: The Innocents, in: Southworth, John: Fools and jesters at the English court, Stroud 1998, S. 48–69. Cf.: Dahhaoui, Yann: Enfant-évêque et fête des fous: un loisir ritualisé pour jeunes clercs ?, in: Gilomen, Hans-Jörg; Schumacher, Beatrice; Tissot, Laurent (Hg.): Temps libre et loisirs du 14e au 20e siècle, Zürich 2005, p. 33-46; Harris, Max: Sacred folly. A new history of the Feast of Fools, New York 2011.

39 Sens, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 33, early 13th c.; Bourquelot, Félix: Office de la Fête des Fous à Sens, Bulletin de la Société archéologique de Sens, 1854, p. 151-170 ; Villetard, Henri, Office de Pierre de Corbeil, Paris, 1907.

40 For detailed descriptions: Dahhaoui, Yann: Le pape de saint Etienne. Fête des Saints-Innocents et imitation du cérémonial pontifical de Besançon, in: Mémoires de cours: études offertes à Agostino Paravicini Bagliani par ses collègues et élèves de l’Université de Lausanne, Lausanne 2008 (Cahiers lausannois d’histoire médiévale 48), S. 141–158. Online: <http://parnaseo.uv.es/Ars/teatresco/Anejos/pape%20de%20Saint-Etienne-[obispillo]_Yann-Dahhaoui.pdf>, Stand: 19.04.2017.

41 Bourquelot, Félix: Office de la Fête des Fous à Sens, Bulletin de la Société archéologique de Sens, 1854, p. 154-155.

42 Heers, Jacques: Fêtes des fous et carnavals, Paris 1983, p. 136-141.

43 Sens, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 33, f. 1: « Ce jour est un jour de joie (...). Ceux qui célèbrent la fête de l’âne ne veulent que de la gaieté ». « Me judice, tristis / Quisquis erit revomendus erit solemnibus istis / Sint hodie procul invidiae, procul omnia moesta. / Laeta volunt, quicumque asinaria festa ».

44 Sens, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 33, f. 27 verso: « Conductus ad Ludarium ».

45 Sens, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 33, f. 28 v°: « Conductus ad Poculum ».

46 Sens, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 33, f. 29: « Conductus ad Prandium ».

47 Luke 6.

48 Luke 16-17.

49 See the detailed ritual by John W. Baldwin, art. cit., p. 647.

50 Cf. Wright, Craig: Music and ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500-1550, Cambridge 1989.

51 John W. Baldwin, art. cit., p. 647.

52 Innocent III, Cum decorem: “Sometimes performances and plays were put on in churches (...), at certain feasts, deacons, priests and subdeacons were bold enough to partake in this folly and buffoonery (...)”, cited by Du Tilliot, Jean-Bénigne Lucotte: Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire de la fête des foux, qui se faisoit autrefois dans plusieurs églises, Lausanne, Geneve 1751, p. 58.

53 M. Du Tilliot, op. cit., p. 102-103. This order led to the birth of the “Company of Mère Folle”: this fraternity consisted of a court of fools led by a sovereign wearing a headdress with bells and bearing a sculpted wooden stick. The company was responsible for organising festive and carnival events in Dijon. The Company of Mère Folle was not an isolated case. Several sociétés joyeuses, abbayes de jeunesse, trade guilds and companies of fools were founded in the 15th and 16th centuries. Cf. Heers, Jacques: Fêtes des fous et carnavals, Paris 1983, p.105 ;Rossiaud, Jacques: La prostitution médiévale, Paris 1988.

54 Gaignebet, Claude; Lajoux, Jean-Dominique: Art profane et religion populaire au Moyen Age, Paris 1985, p. 169.

55 Oxford, Bodleian Library, ms. Bodley 264, f. 84 v°, the Romance of Alexander, c. 1338-44, Bruges. Cf. Ménard, Philippe: Les fous dans la société médiévale. Le témoignage de la littérature au XIIe et au XIIIe siècle, in: Romania 98 (392), 1977, S. 433–459. Online: www.persee.fr, <http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/roma.1977.2537>, Stand: 19.04.2017 et Ménard, Philippe: Les illustrations marginales du Roman d’Alexandre (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 264), in: Braet, Herman; Latré, Guido; Verbeke, Werner (Hg.): Risus mediaevalis. Laughter in medieval literature and art, Leuven 2003 (Mediaevalia Lovaniensia), S. 75–118.

56 Cf. Cruse, Mark: Illuminating the Roman d’Alexandre: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 264. The manuscript as monument, Cambridge 2011; Clouzot, Martine: Musique et performance d’un miroir princier. L’iconographie musicale du Roman d’Alexandre d’Oxford (Bodleian Library, ms. Douce 264, vers 1338-1344), in: Saulnier, Daniel; Livjanic, Katarina; Cazaux-Kowalski, Christelle (Hg.): Lingua mea calamus scribae. Mélanges offerts à madame Marie-Noël Colette, Solesmes 2009, S. 89–100.

57 Bullock-Davies, Constance: Menestrellorum multitudo. Minstrels at a royal feast, Cardiff 1978; Rastall, Richard: Minstrels and Minstrelsy in Household Account Books, in: Dutka, Joanna (Hg.): Records of early English drama: proceedings of the First Colloquium at Erindale College, University of Toronto, 31 August - 3 September 1978, Toronto 1979, S. 3–21.

58 Cf. Wright, Craig: Music at the Court of Burgundy, 1364-1419. A documentary history, Henryville/Ottawa, Binningen 1979 (Musicological Studies, 28); Munrow, David; Previn, André; Kiefe, Laurence: Les Instruments de musique du Moyen Age et de la Renaissance, Paris 1979 ; Marix, Jeanne: Histoire de la musique et des musiciens de la cour de Bourgogne sous le règne de Philippe le Bon (1420-1467), Strasbourg, 1939, réimpr. Genève, Minkoff, 1972.

59 La Haye, Museum Meermanno-Westreenianum, ms. 10 A 11, f. 48 v°.

60 Ibidem, f. 52 v°, La Cité de Dieu, 1475-80.

61 Quéruel, Danielle: Des gestes à la danse : l’exemple de la «Morisque» à la fin du Moyen-Âge, in: Le geste et les gestes au Moyen Âge, Aix-en-Provence 1998 (Senefiance 41), S. 499–517. Online: OpenEdition Books, <http://books.openedition.org/pup/3527>, Stand: 19.04.2017, p. 501-517 (Sénéfiance, 41).

62 Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. fr. 2810, f. 16 v°.

63 Archives nationales, B 1938, f. 72.

64 Archives nationales, B 1938, f. 125: « sept habis de drap de soye et de pluiseurs coulleurs de estrange fachon, propices à danser la morisque et iceux enrichy d'ouvrage de peaulx d'or et d'argent (...) une paire de chausses de toille ou sont faictes testes de serpent de bature d'or party (...) sollers et sonnettes pour a tous iceulx habiz danser la morisque ».

65 Mâle, Émile: L’art religieux de la fin du Moyen âge en France. Étude sur l’iconographie du Moyen âge et sur ses sources d’inspiration, Paris 1949, p. 370; Utzinger, Hélène; Utzinger, Bertrand: Itinéraires des Danses macabres, Chartres 1996.

66 Cf. Schmitt, Jean-Claude: Les revenants. Les vivants et les morts dans la société médiévale, [Paris] 1994, p. 243-47.

67 Londres, British Library, ms. Arundel 83, f. 127, Psalter of Robert De Lisle, c. 1310.

68 Utzinger, Hélène; Utzinger, Bertrand: Itinéraires des Danses macabres, Chartres 1996, p. 228.

69 Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. fr. 25434, La danse macabre de Guyot Marchant, 1484.

70 Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Estampes, Te. 8 Rés. C. 21297-301, f. 23 et 24, La Danse macabre d’Antoine Vérard, 1490.

71 Foucault, Michel: Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique, Paris 1972, p. 26.

72 Foucault, Michel: Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique, Paris 1972, p. 45.

The crazy dancing fool of Psalm

test psalm

Publications

The crazy dancing fool of Psalm

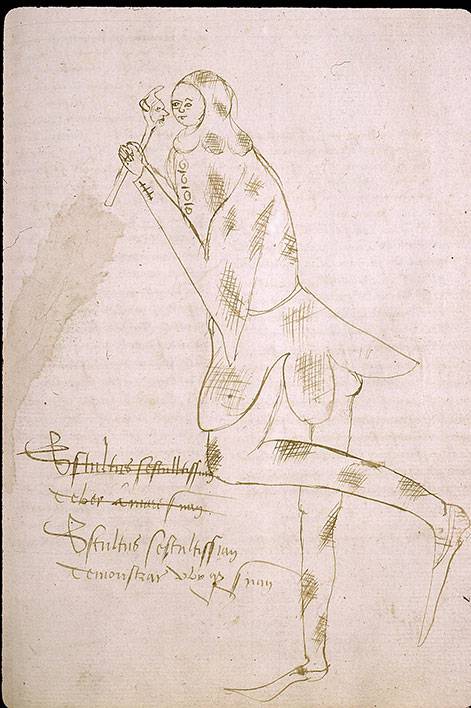

The fool appears in this figure in the manuscripts of the twelfth and especially thirteenth centuries. He dances alone. All opposed him to David, the prime biblical figure. He is defined in opposition to David as a basic figure of mundus inversus. More than 340 documents recorded in the Folimages database1 highlight many visual characteristics that identify this very standardized figure, very frequent in the same manuscripts (in the Psalters and the Books of Hours), and in the same layouts (in the historiated D initial of the Psalm 52 (53) Dixit insipiens).

Agitated, the fool exceed the frame of the image while David thrones in an architectural structure, or even is not represented at all. The fool is half naked, in a shirt or wrapped in a sheet. He is shaggy or tonsured, wearing a hood or a bonnet and a single-colored or two-colored clothing, yellow, green and/or pink. David has a beautiful coat and a crown or a scepter. The fool is standing, gesturing on the right and left, crosses or lifts a leg, raises a hand or arm, turns back. Next to him, David is contemplating, standing, sitting or kneeling, fronting, facing the fool or facing God. The fool is dancing, hoping, shouting, grimacing, blasphemating (“Non est Deus”), ringing bells, talking to his hobby, pointing, brandishing a stick or a club, biting or holding a round object. In contrast, David is calmly looking at the fool, playing his harp, praying and speaking to God, introducing the Psalms. The fool personifies sin and vice; David embodies the moral virtue, the wisdom. This Psalm’s fool is the Fool’s enduring archetype.

1 his database, currently being developed at the UMR ARTEHIS (Dijon, University of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté), lists and analyzes medieval images of madness.

Le chevalier et le fou (2012)

Alicia Servier:

Le chevalier et le fou. Du personnage à la figure dans les enluminures du Lancelot du Lac (XIIIe – XVe siècle), 2012.

La représentation de l’insipiens (2000)

Angelika Gross:

La représentation de l’insipiens et la catégorisation esthétique et morale des parties corporelles dans le Buch Der Natur de Konrad von Megenberg, 2000.

Sémiotique de la tonsure (1995)

Angelika Gross, Jacqueline Thibault-Schaefer:

Sémiotique de la tonsure, de l’«insipiens» à Tristan et aux fous de Dieu, 1995.

L’idée de la folie en texte et en image (1993)

Angelika Gross:

L’idée de la folie en texte et en image. Sébastian Brandt et l’insipiens, 1993.

L’exégèse iconographique du terme «insipiens» (1989)

Angelika Gross:

L’exégèse iconographique du terme 'insipiens' du Psaume 52, 1989.

Images

The Walters Art Museum

Baltimore:

The Walters Art Museum: 14 images

Psautier (Carrow Psalter), 1250 environ

https://issuu.com/the-walters-art-museum/docs/w34/248?e=1251836/5099729

Psautier (Carrow Psalter), 1250 environ

http://art.thewalters.org/detail/29552/king-stabbing-self-with-sword-2/

Psautier (Psalter of Jernoul de Camphaing), 1250-1275

http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/W42/data/W.42/sap/W42_000129_sap.jpg

Psautier-livre d'Heures franciscain à l'usage de Cologne, 1275-1299

http://art.thewalters.org/detail/34127/initial-d-with-a-fool-below-the-face-of-god-2/

Psautier et office de la mort, 1265-1280

http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/W117/data/W.117/sap/W117_000113_sap.jpg

Psautier, 1250-1275

Psautier liturgique franciscain, 1275-1299

Psautier, 1275-1300 environ

Psautier, 1300 environ

Psautier, 1310-1320 environ

http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/W110/data/W.110/sap/W110_000186_sap.jpg

Psautier et livre d'Heures, 1315-1325 environ

http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/W82/data/W.82/sap/W82_000107_sap.jpg

Bréviaire à l'usage de Liège, 1420 environ

http://art.thewalters.org/detail/95044/leaf-from-breviary-psalm-52-initial-d-with-the-fool/

Bréviaire, 1430 environ

http://art.thewalters.org/detail/38763/leaf-from-breviary-11/

British Library

London:

British Library: 32 images

This corpus is also accessible via the search form of Europeana, with the search terms "Fool AND psalm AND The British Library".

Psautier, 1250 environ

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=30560

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier, 1250-1275

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=8725

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Bible of William of Devon, 1250-1275

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=29827

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Bible, 1250-1275

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=6426

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier (The York Psalter), 1260 environ

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_54179_f046r

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Bible (The Brantwood Bible), 1260 environ

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=45494

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Bréviaire (The Coldingham Breviary), 1270-1280

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=28670

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier (The Huth Psalter), 1275-1299

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=57603

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier, 1275-1299

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=7805

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier et livre d'Heures à l'usage de Saint-Omer, 1276

http://www.bl.uk/IllImages/Kslides%5Cbig/K066/K066841.jpg

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier et livre d'Heures à l'usage d'Arras, 1300 environ

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=11493

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier et livre d'Heures à l'usage d'Arras, 1300 environ

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=5804

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Bréviaire à l'usage de Verdun (partie hiver). Bréviaire de Renaud de Bar ou Bréviaire de Marguerite de Bar, 1302-1303

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=6659

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier de Robert de Lisle, 1310 environ

https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=7084

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier (The Queen Mary Psalter), 1310-1320

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=royal_ms_2_b_vii_f150v

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier , 1310-1340 environ

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=1955

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1320-1340 environ

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=7816

(© British Library Board)

Bréviaire à l'usage de Sarum (The Stowe Breviary) et ordinaire, 1322-1383

https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=7684

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Luttrell Psalter, 1325 environ

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_42130_f028r

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier (The St Omer Psalter), 1330-1440 environ

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=yates_thompson_ms_14_f057v

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1350-1356 environ

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=46867

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1357

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=42201

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier (fragments), 1375-1399

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=39516

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier (The Princess Joan Psalter), 1400-1425

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=41009

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1400-1425

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=37773

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Bible (The Big or Great Bible), 1400-1425

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=38433

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1411 environ

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=46521

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Bréviaire de Jean sans Peur, 1413-1419

https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=20907

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1418-1420

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=46381

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Livre d’Heures, 1460 environ

https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=28153

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Decameron de Boccace, trad. de Laurent Premierfait, 1475 environ

http://images.cdn.bridgemanimages.com/api/1.0/image/600wm.BL.9096520.7055475/253730.jpg

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier, 1475-1525

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=37320

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

The J. Paul Getty Museum

Los Angeles:

The J. Paul Getty Museum: 7 images

Psautier (Wenceslaus Psalter), 1250- 1260 environ

This image is available for download, without charge, under the Getty's Open Content Program.

Bible, 1250-1262

This image is available for download, without charge, under the Getty's Open Content Program.

Psautier (Bute Master), 1270-1280 environ

This image is available for download, without charge, under the Getty's Open Content Program.

Psautier (Bute Psalter), 1270-1280 environ

This image is available for download, without charge, under the Getty's Open Content Program.

Bible, 1280-1290 environ

This image is available for download, without charge, under the Getty's Open Content Program.

Bréviaire, 1320-1325 environ

This image is available for download, without charge, under the Getty's Open Content Program.

Bible historiale, 1360-1370 environ

This image is available for download, without charge, under the Getty's Open Content Program.

The Pierpont Morgan Library

New York:

The Pierpont Morgan Library: 42 images

Psautier, 1220-1230

Bible, 1225-1250

Bible, 1245-1250

Bible de Maciejowski, 1250 environ

Psautier, 1250-1299

Psautier, 1250-1299

Bible, 1260 environ

Bible, 1260 environ

Bible, 1265 environ

Psautier (Windmill Psalter), 1270 environ

Psautier de Cuerden, 1270 environ

Psautier de Cuerden, 1270 environ

Psautier, 1275-1299

Bible, 1275-1299

Psautier et livre d'Heures, 1280 environ

Bréviaire, 1285-1297

Bible, 1287-1300 environ

Psautier, 1297-1310

Psautier, 1300-1325

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1300-1325

Psautier, 1300-1399

Psautier, 1310-1320

Bréviaire, 1315-1325 environ

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1325 environ

Bréviaire, 1350 environ

Psautier et livre d’Heures à l’usage de Metz, 1370-1380

Bible, 1415 environ

Psautier et livre d'Heures, 1455-1460

Psautier et livre d'Heures, 1460 environ

Bréviaire (Piccolomini breviary), 1475 environ

Bréviaire, 1481

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Paris:

Bibliothèque nationale de France: 26 images

Psautier de Blanche de Castille, 1250 environ

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b105065665/f138.image

This work is free of known copyright restrictions.

Psautier de saint Louis, 1250 environ

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-07904244&E=JPEG&Deb=1&Fin=1&Param=C

Bible (dite Bible de saint Louis), 1260-1275

Psautier, 1275-1299

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9067924n/f122.image

This work is free of known copyright restrictions.

Psautier, 1275-1299

Livre d’Heures, 1275-1325

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-07848418&E=JPEG&Deb=1&Fin=1&Param=C

Petrus Comestor, Bible historiale, traduction de Guyard des Moulins, 1300-1399

Petrus Comestor, Bible historiale, traduction de Guyard des Moulins, 1300-1399

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-8100228&E=JPEG&Deb=144&Fin=144&Param=C

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1300-1399

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1300-1399

Guyard des Moulins, Bible historiale, 1300-1399

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-8100028&E=JPEG&Deb=84&Fin=84&Param=C

Bible (Biblia Philippi Pulchri, regis Francorum), 1301-1315

Bréviaire à l'usage des frères mineurs (Bréviaire dit de Jeanne de Bourbon), 1330-1350

Petrus Comestor, Bible historiale, traduction de Guyard des Moulins, 1350-1375

Psautier et livre d'Heures à l'usage de la Sainte-Chapelle de Paris, 1360-1400

Psautier de Jean de Berry, 1386-1390 environ

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=8002379&E=JPEG&Deb=1&Fin=1&Param=B

Grande Bible historiale complétée, 1395-1401

« L'un des quatre Volumes de l'Istoire de la Table Ronde, nommé le Livre de Tristan », translaté par « Luce, chevalier et sire du chastel du Gad », 1400-1499

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-8100108&E=JPEG&Deb=91&Fin=91&Param=C

Le Roman de Tristan, 1400-1499

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-8100107&E=JPEG&Deb=88&Fin=88&Param=C

Psautier de Charles VIII, 1450-1500

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-07804649&E=JPEG&Deb=1&Fin=1&Param=C

Diurnal franciscain à l'usage d'Angers, 1451-1462

Psautier à l'usage des frères mineurs, dit Psautier-hymnaire de Ferdinand Ier d'Aragon, 1475

« Des douze Perilz d'enfer », traduction [de Pierre de Caillemesnil], 1501-1600

Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève

Paris:

Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, 17 images

Bible, 1175-1199

http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht15/IRHT_020504-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Bible, 1220-1230 environ

http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht16/IRHT_030282-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Bible, 1225-1235 environ

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht16/IRHT_029731-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Petrus Lombardus, Commentarius in psalmos, 1225-1250

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht15/IRHT_022796-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Psautier à l'usage de l'abbaye de Sainte-Croix de Poitiers, 1239 après

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/ouvrages/ouvrages.php?imageInd=46&id=3427 (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Psautier à l'usage de l'abbaye de Sainte-Elisabeth de Genlis, 1250-1260 environ

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/ouvrages/ouvrages.php?imageInd=32&id=3425 (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Bible, 1266-1299

http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/ouvrages/ouvrages.php?imageInd=75&id=3093 (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Bible, 1275-1299

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht15/IRHT_020898-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Bible, 1275-1299

http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht16/IRHT_029893-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Bible, 1300-1325

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht16/IRHT_031839-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Bible, 1300-1399

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht16/IRHT_029488-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Petrus Comestor, Bible historiale, 1320-1337

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht15/IRHT_021537-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Petrus Comestor, Bible historiale, 1330 environ

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht15/IRHT_021828-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Psautier-hymnaire à l'usage du prieuré de Sainte-Barbe-en-Auge, 1400-1450 ?

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht15/IRHT_024047-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Recueil de mystères et de pièces relatives à plusieurs saints, 1400-1499

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht16/IRHT_029337-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Bréviaire à l'usage du prieuré Saint-Lô de Rouen, 1500-1525

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht16/IRHT_030714-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

Bréviaire à l'usage du prieuré Saint-Lô de Rouen, 1500-1525

http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht16/IRHT_030776-p.jpg (© Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, cliché IRHT)

The fool of the Feast of Fools

Publications

The fool of the Feast of Fools

The fool is no longer isolated, it is linked to a group. He participates in gesticulations, dancing and crowd disturbances authorized by the Church. He is an actor of ecclesiastical and secular ritual organized where everything is reversed for a few days between St. Etienne's Day and the New Year.

The fool takes part in a ritual organized by the high clergy, but celebrated by the lower clergy, by the deacons and the altar boys. He joins the dances, the games and the satirical shows, the processions and the parody songs of the Office. He shares the feast offered to children, caricature of the Eucharist. He participates in the Feast of the Ass (Donkey Procession, Donkey Office, Donkey Prose) that distorts the Christmas story. As the main figure of the Bishop of Fools, with its bells and foibles, he pastiches the role of the bishop, his attributes and his functions.

Enfant-évêque et fête des fous (2005)

Yann Dahhaoui:

Enfant-évêque et fête des fous. Un loisir ritualisé pour jeunes clercs?, Zürich 2005.

La Fête des fous dans le nord de la France (XIVe-XVIe) (2002)

Pierre Emmanuel Guilleray:

La Fête des fous dans le nord de la France (XIVe-XVIe), Paris 2002.

La Fête des Fous dans l’Encyclopédie (1998)

Renée Relange:

La Fête des Fous dans l’Encyclopédie, 15.10.1998.

Office de Pierre de Corbeil (1907)

Henri Villetard:

Office de Pierre de Corbeil (Office de la circoncision) improprement appelé Office des Fous, Paris 1907.

Notice sur les fêtes des ânes et des fous (1823-1904)

Jacques-Xavier Carré de Busserolle:

Notice sur les fêtes des ânes et des fous qui se célébraient au moyen âge dans un grand nombre d’églises, et notamment à Rouen, à Beauvais, à Autun et à Sens, Rouen (1823-1904).

Office de la Fête des Fous à Sens (1854)

Félix Bourquelot:

Office de la Fête des Fous à Sens. Introduction, textes et notes, Sens 1854.

Memoires pour servir à l’histoire de la fête des foux (1741)

Jean-Bénigne Lucotte Du Tilliot:

Memoires pour servir à l’histoire de la fête des foux, qui se faisoit autrefois dans plusieurs églises, Lausanne, Genève 1741.

Images

Images

Medieval images of the feast of the fools are extremely rare. Two documents related to this feast are recorded in the Folimages database (Dijon, Artehis, M. Clouzot, M.-J. Gasse-Grandjean).

IRHT, Enluminures

Paris:

IRHT, Enluminures, 2 images

Graduel, 1200-1299 (dessin en marge inférieure pour la fête des fous)

http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht6/IRHT_102351-p.jpg (© Ville de Provins et © IRHT-CNRS )

Chorus dit de la Mère folle, 1500-1525

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht6/IRHT_094980-p.jpg (© BM Dijon)

http://www.culture.gouv.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht6/IRHT_094981-p.jpg (© BM Dijon)

Music

Polyphonies de Notre-Dame de Paris (2013)

Ensemble Diabolus in Musica:

Polyphonies de Notre-Dame de Paris, XIIe-XIIIe siècles, ADF-Bayard Musique, 2013.

Perotin and the Ars Antiqua (2007)

The Hilliard Ensemble:

Perotin and the Ars Antiqua, Coro 2007.

Pérotin et l’Ecole Notre-Dame de Paris (2006)

Ensemble Gilles Binchois:

Pérotin et l’Ecole Notre-Dame de Paris, 1160-1245, 2006.

La Fête des Fous (2005)

Emmanuel Bonnardot:

La Fête des Fous, Calliope, 2005.

La Fête de l’Âne (1998)

Clemencic Consort:

La Fête de l’Âne, Harmonia Mundi, 1998.

Messe du Jour de Noël (1996)

Ensemble Organum, Marcel Peres:

Messe du Jour de Noël, Harmonia Mundi, 1996.

The fool in court dances

Publications

The fool in court dances

The fool is coopted and displayed by the secular power. He is advertising the mundus inversus for the many. He participates in yard games in the middle of jugglers, minstrels and animals. He shrugs, jumps in opposite directions, it is driven in the impossible farandoles of Alexander’s novel. Sometimes the fool dances naked or appears transvestite as a wild man or with a turban in the oriental fashion and bright colors.

Images de la folie au tournant du Moyen Âge et de la Renaissance (2012)

Guillaume Berthon, Xavier Leroux:

Images de la folie au tournant du Moyen Âge et de la Renaissance, 2012.

Roi des ménestrels, ménestrel du roi ? (2010)

Martine Clouzot:

Roi des ménestrels, ménestrel du roi ? Statuts, fonctions et modèles d’une autre royauté aux XIIIe, XIVe et XVe siècles, Paris 2010.

Sonare et ballare

Martine Clouzot:

Sonare et ballare. Musique et danse dans les manuscrits de la fin du Moyen Âge

Le fou du duc à la cour de Bourgogne (2003)

Martine Clouzot:

Le fou du duc à la cour de Bourgogne aux XIVe et XVe siècles, 2003.

Fous du roi et roi fou (2002)

Bernard Guenée:

Fous du roi et roi fou. Quelle place eurent les fous à la cour de Charles VI ?, 2002.

Des gestes à la danse (1998)

Danielle Quéruel:

Des gestes à la danse : l’exemple de la «Morisque» à la fin du Moyen-Âge, 1998.

Le Fol dans les moralités du Moyen Age (1985)

Margarete Newels:

Le Fol dans les moralités du Moyen Age, 1985.

Images

British Library

London:

British Library, 4 images.

Cas nobles hommes et femmes maleureux de Boccace , traduit par Laurent Premierfait, 1470-1483

https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=50625

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Les chroniques de Froissart, 1475-1483

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=40128

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Chroniques de France et d’Angleterre de Jean Froissart, 1475-1499

https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=43437

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

Psautier (The Psalter of Henry VIII), 1540-1541

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=47741

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

This image identified by the The British Library, is free of known copyright restrictions. For further guidance on use of public domain images please click here.

The Pierpont Morgan Library

New York:

The Pierpont Morgan Library, 2 images

John Gower, Confessio amantis, 1470 environ

Psautier et livre d'Heures, 1482 Library

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Paris:

Bibliothèque nationale de France, 12 images

Chroniques de Jean Froissart, 1400-1499

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10538041t/f962.highres

Dits et Faits des Romains de Valère-Maxime, 1400-1499

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-8100205&E=JPEG&Deb=1&Fin=1&Param=C

Grandes Chroniques de Jean Froissart, 1400-1499

Le Roman de Tristan, 1400-1499

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-8100107&E=JPEG&Deb=89&Fin=89&Param=C

Roman d’Alexandre, de Jean Wauquelin, 1400-1499

http://gallicalabs.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000083z/f106.item

« L'un des quatre Volumes de l'Istoire de la Table Ronde, nommé le Livre de Tristan », translaté par « LUCE, chevalier et sire du chastel DU GAD », 1400-1499

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-8100108&E=JPEG&Deb=89&Fin=89&Param=C

« L'un des quatre Volumes de l'Istoire de la Table Ronde, nommé le Livre de Tristan », translaté par « LUCE, chevalier et sire du chastel DU GAD », 1400-1499

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-8100108&E=JPEG&Deb=91&Fin=91&Param=C

Speculum historiale de Vincent de Beauvais, traduit par Jean de Vignay, 1463

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-8100046&E=JPEG&Deb=111&Fin=111&Param=C

Messire Lancelot du Lac, par Gaultier, 1470

http://gallicalabs.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8527587p/f83.image (© Paris, Bnf)

Chroniques de France et d’Angleterre de Jean Wavrin, 1470 environ

Historiae Alexandri Magni de Quinte Curce, 1475-1499

http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=IFN-8100013&E=JPEG&Deb=14&Fin=14&Param=C

Roman d’Arthur et de Guiron le Courtois, 1475-1499

Autres dépôts

Oxford, Philadelphie, Vienne, la Haye:

Autres dépôts, 5 images

Bible, 1450-1475

https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/1162 (© Free Library of Philadelphia, Digital Collections)

Chroniques de Jean de Wavrin, 1470 environ

http://archiv.onb.ac.at:1801/webclient/StreamGate?folder_id=200&dvs=1485248589500~984 (© ÖNB/Wien)

Chroniques de Jean de Wavrin, 1470 environ

http://archiv.onb.ac.at:1801/webclient/StreamGate?folder_id=200&dvs=1485248765536~190 (© ÖNB/Wien)

La Cité de Dieu de Saint Augustin, Livres I-X, trad. Raoul de Presles, 1475-1480

http://manuscripts.kb.nl/zoom/BYVANCKB%3Amimi_mmw_10a11%3A048v_min_1

Music

Instruments de musique du Moyen Âge (2007)

David Munrow & Early Music Consort of London:

Instruments de musique du Moyen Âge, 2007.

Vox Aurea (1999)

Obsidianne, Emmanuel Bonnardot:

Vox Aurea – Ockeghem, Motets ; Faugues, Missa La Basse Danse, 1999.

Musique à danser de la Renaissance française (1995)

Compagnie Maître Guillaume:

Musique à danser de la Renaissance française, 1995.

La Danse à la Cour de Bourgogne (1988)

La Maurache:

La Danse à la Cour de Bourgogne, 1988.

The fool in the dance of death

Publications